Presencing

'We are now out at the very, very edge of the textual record': Lesley Harrison on the poetry of Stewart Sanderson

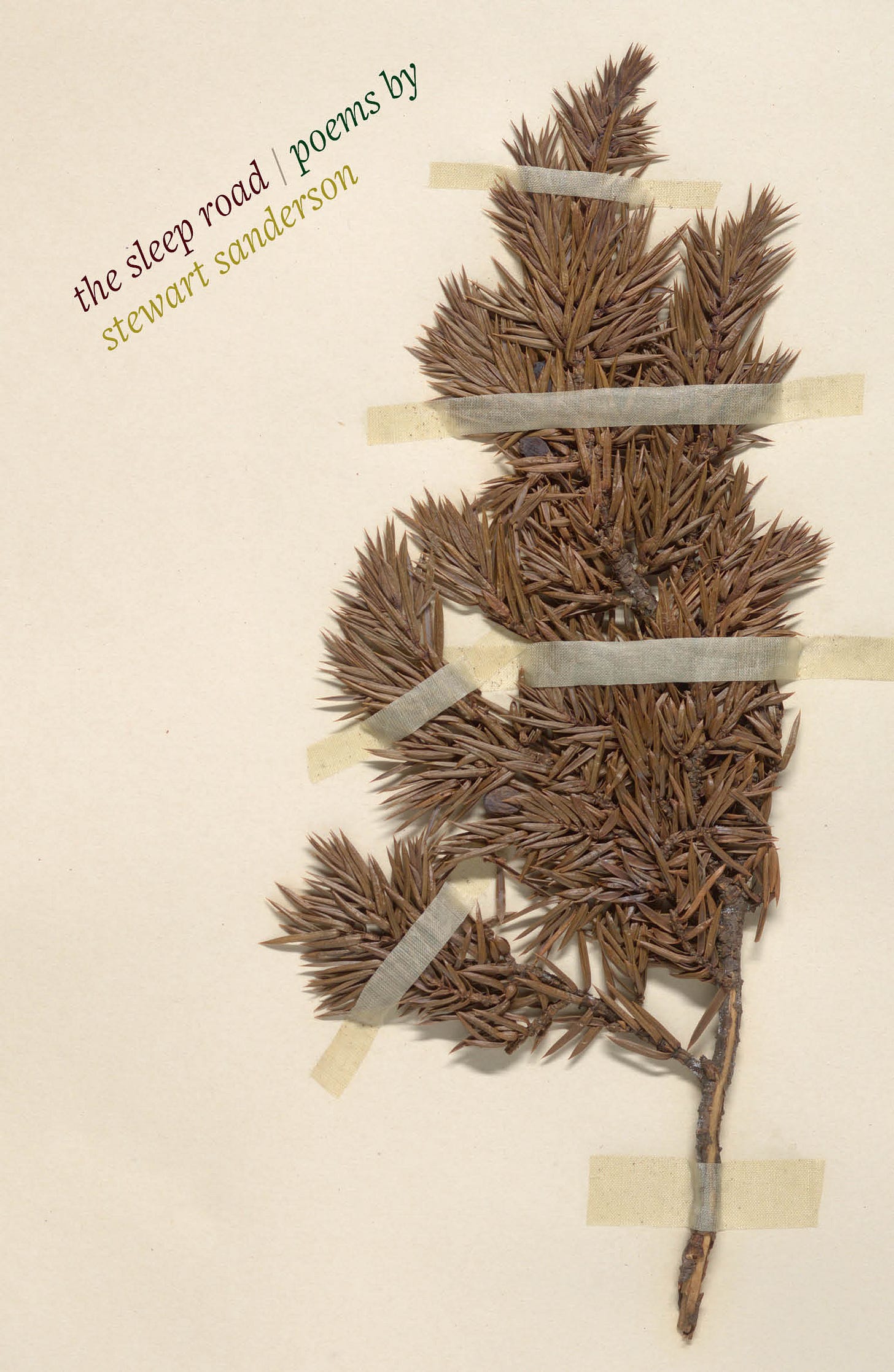

I am the first to admit I am a bit slow off the mark at times. But I don’t know how I missed The Sleep Road by Stewart Sanderson (Tapsalteerie, 2021) first time round, and I am much obliged to our own John Glenday for flagging it up.

Stewart Sanderson’s first full collection is set in the half-explored, half-defined borderlands around our history and our language, and he uses the tools and techniques of poetry meticulously to conjure them. These poems are full of the matter of landscape - rock, turf, water - but equally tangible here is the matter of language itself:

UNLAND

I know a word

for the weather-beaten place

a word for where nothing

will grow but what

we cannot eat

for where the land

is worn at and washed

away by waters

which erode

soil as the stillness

does this word for where

no nation matters

‘Unland’ is an old Scots word for a designated area of land which is non-arable, or unfit for cultivation. This theme shapes the whole collection – not just as a setting, but as metaphor for the porous nature of our borders, real and imagined, and for the ongoing process of (re)negotiating our sense of identity, and how this is bound up with attachment to place. This is a psychic border country, where threads and scraps of other/older languages and voices blow through and merge with our own.

Take for example the poem ‘An Unstatistical Account’. From 1791 to 1845, at the height of the Scottish Enlightenment, the ministers of Scotland’s 938 parishes were asked to describe and appraise aspects of their community – agriculture, industry, ancient monuments, communities, landscape. These compiled Statistical Accounts were to provide a quantitative and qualitative baseline of our overall “quantum of happiness”, as a basis for economic improvement. By lifting phrases from the ministers’ accounts, Sanderson creates a real ‘hymn to place’, a testament of identity and estrangement, of pride and bred-in-the-bone Calvinist caution. Which makes it wry, moving and incredibly contemporary.

this people

they are like other people

poor people

frugal and laborious people

common people

the very lowest of people

people in general

our own people

The National Library of Scotland holds a manuscript of music for a mandora, an early form of lute popular in the 1600s in the drawing rooms of Europe. This manuscript belonged to John Skene, keeper of the Hallyards Castle in Kirkliston in 1700, though it might have been quite old when he acquired it. This text is noted for having the earliest transcription of the tune for ‘The Flowers of the Forest’, a song lamenting the border battle at Flodden in Northumberland in 1513 – which would have been within living memory at the time the manuscript was written.

You can hear this tune played on an actual mandora here:

The words we know – and, in fact, the tune too – came later. (Michael Nyman adapted the original melody for the track ‘Dreams of a Journey’ in his score for the film The Piano. I can just about hear it:

In his poem ‘Those Unheard’, Sanderson has used ‘reverse musical cryptograms’ to generate poems from three of the songs in the Skene manuscript. They hint at escape and hiding, close to the ground.

Grief, get away –

be yourself elsewhere.

Don’t bide here

gathering like rainclouds.

Now gladness hides

beyond dark elms.

Dust whispers

and grows greedy.

Yesterday evening

their shadows met us.

Dusk brings voices

until echoes die.

Returning singly

girls stand around waiting.

Anemones utter

aicill underfoot.

An ‘aicill’ is a rhyme scheme in which the final word of one line rhymes with a word within in the next; I’m guessing that Sanderson has used this word to flag up to us his deployment of the scheme here (‘elsewhere’/‘here’, ‘clouds’/’ hides and so on) to enhance our sense of lingering, of things never being finished. Or maybe the ‘reverse musical cryptogram’ led him to this point? Many of the poems in this collection follow a formal rhyme scheme, and occasionally (to my ear) this becomes a bit of a burden to him, with the odd weak line completing the jigsaw. However these moments only announce themselves because otherwise his use of rhyme can be so deft, blurring boundaries of meaning, providing grace and forward motion while they work on your subconscious.

Of course the great benefit of using any device to generate extracts from a text is that your own poetic voice can be taken over, your presence as poet-intermediate apparently removed. In ‘A Sense of Beauty’, Sanderson employs two sets of letters from the same year to create not so much a dialogue between two writers, but something like a shared reverie, despite the many miles and distances between them. The note for ‘The Sense of Beauty’ tells us that the poem pairs ‘natural pentameters’ from the letters of John Keats with extracts from the last letter of the Radical martyr, Andrew Hardie, written in prison just before he was executed.

Hardie was convicted for his part in the organisation of protests at the Carron Ironworks. The manufacturing process had been mechanised, and very quickly the whole community of artisan workers became redundant. Hardie had led a claim for the rights of the workers to be recognised. He was executed in September 1820; Keats, aware he himself was ailing when he wrote these letters, died a few months later.

They then asked me what rights I wanted

my mind has been at work all over the world

I said annual Parliaments, and election by ballot

with health and hope we should be content to live

they looked at one another, and said nothing

it is probable you will hear some complaints against me

I am, Sir, your most obedient servant

I should have liked to cross the water with you

In ‘The Sense of Beauty’, the voices of Hardy and Keats have been extracted and reassembled for us. Both are thinking outward from themselves, and of this world without themselves. Around this time, Keats had written in a letter to a friend: ‘I am certain of nothing but the holiness of the Heart’s affections and the truth of the imagination. What imagination seizes as Beauty must be truth.’ Again, I find this pairing of lives and words incredibly moving. Both men are thinking of their deaths, so close now that they can almost see the land beyond.

This is Sanderson’s great gift as a poet, I think. In his creative interpretations of older texts, he stands us shoulder-to-shoulder with the original writers, and the people on whose behalf they are writing. They are both ‘then’ and ‘now’.

This presencing also appears in the three poems of ‘Ogham’. Each addresses a carved stone, and in each we are alongside the original scribe, crouched in that particular spot, composing and carving while woodsmoke and lichen are already starting to obscure our words. But it is the placing of a poem - this precise location, and the decision of the scribe to carve just along this line – that is important. The meaning of the inscription is a thinking within this place. Here we are, knee-deep in a peat bog with a Shetland squall running down our necks:

How the rain

conspires against

consonant and

vowel as it

veers in

everlastingly

voluminous and

vulture-like.

We are now out at the very, very edge of the textual record, and maybe the beginning of our cultural memory, when language and writing began to give us a notion of ourselves. The writing becomes the weather; whatever the runes are saying, their presence is as much a matter of this place as the weather or this lump of slate or anything else.

‘Sleep is the other half of us ... It is us, in our absence’. (Marie Darrieussecq, Sleeplessness). These poems explore paths we’re not quite aware we are following; and the tracks we trace, half-consciously, into the future.

Stewart Sanderson’s latest collection is Weathershaker (Tapsalteerie, 2025)

Sanderson translates Hart Crane:

Quite often, cold

from the cold sea

the seagull flies

round and round

the harbour. The

waters are bound

but not he. He

looks a bit

like Freedom.

I have to say I love reviews a few years late, because then it's much easier to find a second-hand copy online (which for those of us overseas, can often mean any copy at all, in the case of small presses). Thanks.