Writing the Last Word

Lesley Harrison on the poetry of Inger Christensen

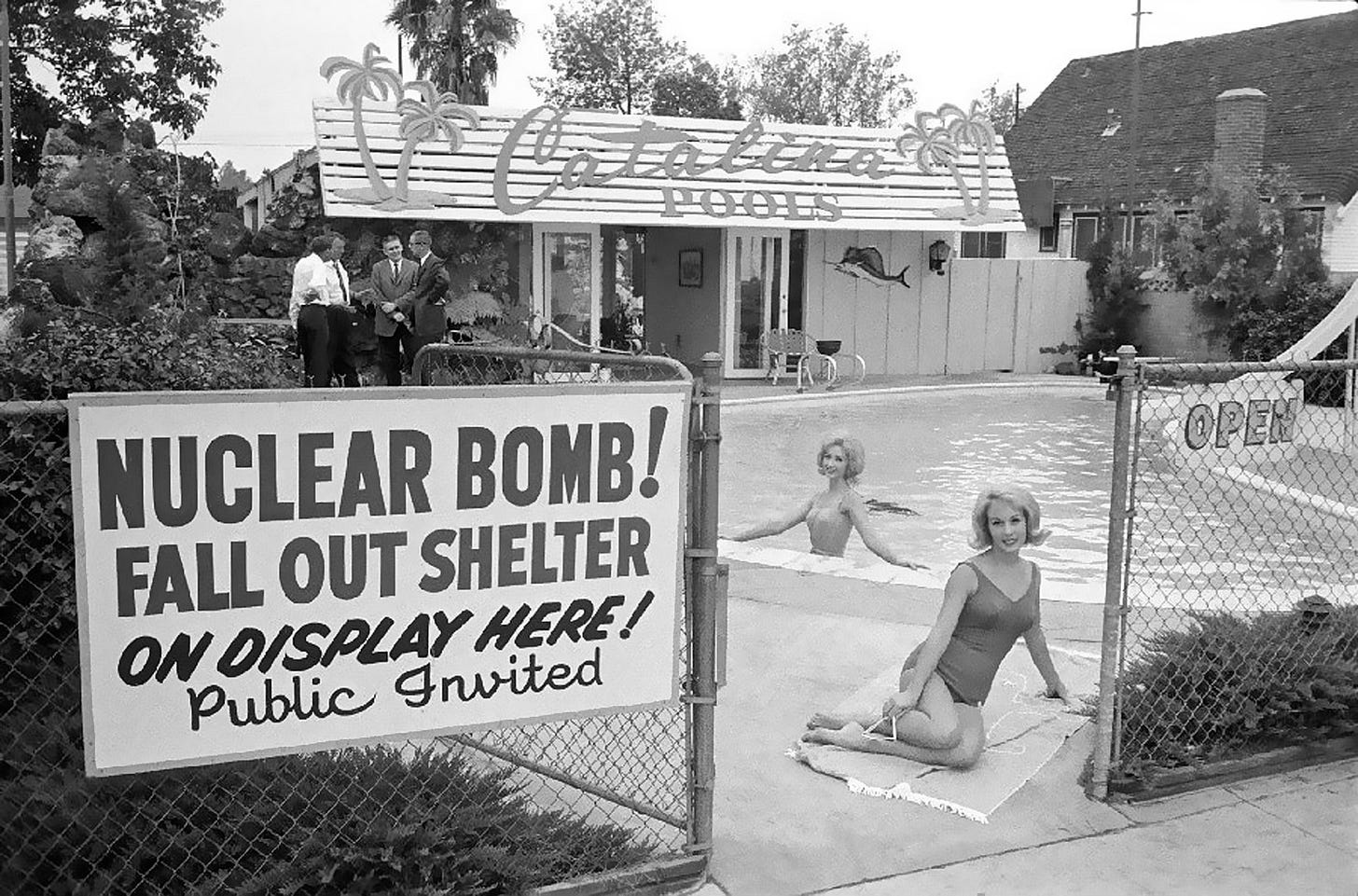

Inger Christensen’s long poem alphabet was published in 1981. Its backdrop, and the backdrop to much of her work, is the never-ending Cold War and the real existential threat of nuclear conflict. Denmark, “a strategic giant” according to Nato and “a weak link in the chain” according to the Soviet Union, lay in a highly vulnerable position between East and West. “I did not set out to write an apocalypse poem,” said Christensen; but as the sequence progresses, ideas of alienation and ecological collapse force their way in. Its world is shaped by a sense that we are living with a profound environmental grief (daily life in Denmark at the time was punctuated with preparations for nuclear attack). Yet there is also a human process by which we knit together our ordinary world in all its profusion of living things and objects that hold meaning for us, and from which we create some kind of hope.

To structure its progression, she imports two types of ordering: the Fibonacci sequence to determine the number of lines for each poem, and the alphabet, to summon its content. Together they determine the production of the text and how it progresses. These external devices also insert a sense of detachment, a lack of agency. No ideas but in things : alphabet is a litany, a self-conscious rehearsal of familiar things that are called up both to keep them present and to grieve for their loss.

1

apricot trees exist, apricot trees exist

During her life, Christensen set out her own thinking on the poetic use of language in a series of essays (collected as The Condition of Secrecy, trans. 2018). Nouns, she says, are superficially discrete – “like crystals, each enclosing its own piece of knowledge about the world. But examine them thoroughly, in all their degrees of transparency”. A word vanishes as soon as it is said, “but your thoughts and feelings are already on their way to the farthest corners of the world”. Within these lists there is assonance, visual and aural pattern and so on – all the stuff of poetry – but as a tool to link one word and the next, or one on the line above, or the next stanza. Each section begins with a domestic object, but others are conjured from the subconscious by words within words, by half rhyme, by sound clusters, by memories. There are oblique and then more explicit allusions to chemical and nuclear war.

4

doves exist, dreamers, and dolls;

killers exist, and doves, and doves;

haze, dioxin, and days; days

exist, days and death; and poems

exist; poems, days, death

A note : I am reading Susannah Nied’s Bloodaxe translation (2000) which I find utterly hypnotic. In the transposition from Danish to English, some of the alphabetical grouping is lost (“killers” in Danish is dræbere). But Nied’s deployment of sound pattern, visual rhyme and consonant clusters create a fluent, sonorous poem-world that can only be doing justice to Christensen’s 1981 original.

The sequence reaches its crisis in the advent of actual war, and from then on we are living in its aftermath, a world of surreal, perpetual decay :

as if the hydrogen

at the stars’ cores

turned white here on earth

your brain can

feel white

as if someone had

pleated up time

pushed it in

through the door of

a room

The last poem is number 14, the letter ‘n’, with 610 lines. Why does she stop here? When asked in an interview, Christensen herself said (perhaps not quite seriously) that 610 lines is quite long, really. In fact it stops at around 330. Marianne Ølholm suggests that the logic of the Fibonacci series has by this point created “an uncontrollable production of text which in the end causes the cataloguing and ordering endeavour of the alphabetisation to collapse” (2018). The poems, however, remain careful and poised, almost hesitant now. Sometimes there are dates beside stanzas. In Condition of Secrecy, Christensen quotes the French poet Bernard Noël: “We write in order to get to the last word, but the act of writing constantly delays that. In reality, the last word can be anywhere at all in what we write.”

Maurice Blanchot published The Writing of the Disaster in 1980, one year before Christensen’s alphabet appeared. Blanchot was concerned with the whole machinery of war in the 20th century. World War II, the Holocaust and the horrific power of nuclear weaponry have created a sense of death and foreboding, he argued, and a grief at our loss of agency, that is now embedded in our collective subconscious.

Near the end of alphabet, in one of the longest and most moving sections, we loop the planet endlessly, seeing everything but without detail.

so here I stand by the Barents Sea

out there is the Barents Sea

and it looks like the Barents Sea

is always alone with the Barents Sea

but around behind the Barents Sea

the water stops at Spitzbergen

and just behind Spitzbergen

....

Why does this book obsess me now?

On 26 September 1983, at the height of the Cold War, the Soviet nuclear early warning system identified an incoming intercontinental ballistic missile with four more missiles behind it, launched from US territory. Rather than react immediately, the engineer on duty at the Russian command centre decided to wait for a second confirmation – something about it seemed odd – and in doing so he prevented a massive retaliatory nuclear strike against the United States and its NATO allies, and the onset of what surely would have become a full-scale tit-for-tat nuclear war. The satellite warning system had indeed malfunctioned; we all woke up next morning, alive.

Bizarrely, I have two separate memories of this event. In the first I have just walked in to my 9am Higher Chemistry class. Everyone is there and no-one is working; we are wandering round in a mix of horror and forced teenage hysteria, laughing and gawping at how close we have just come to being vaporised in our own beds. In the second, I am much younger. I have been woken up by my parents and brother who were gouging a hole in my bedroom wall and are now climbing out into a tunnel. Nuclear war was announced during the night, and they are in a rush to leave. For some reason, I have to stay behind. We say our goodbyes quickly, and then I am standing my bedroom in an icy cold, hiding behind the curtain as the room grows grey with the dawn.

Neither of these events actually happened – by 1983 I had finished school and left home – but still, both chill me whenever they come to mind. Grief and foreboding. How weird that these have retrospectively implanted themselves in my childhood imaginary.

Lesley Harrison will be teaching on the ‘Writing With’ course - starting 20th September. Tickets still available. Get all the details at northseapoets.com 🌊

*

We welcome comments! But please keep it relevant, please post nothing offensive and nothing personal, and please don’t police others’ speech. If you find you have lots to say, do consider linking to your own Substack essay.

What a wonderful post. I can't read the Danish but have just jumped to order the poem - I can absolutely see why these images come crashing in and have relevance right now, in the new context of a climate crisis. And this, on the act of writing - 'In reality, the last word can be anywhere at all in what we write.' I mean, - hallelujah someone else articulated how hard it is to get to the end, or to know what an end even is.

For years I've dreamt of masses of planes flying high across the sky. A post-war child with vivid fears. Today I read of mass drone attacks on Ukraine. Now l know it was strange foresight. Scary.