The Burns Identity

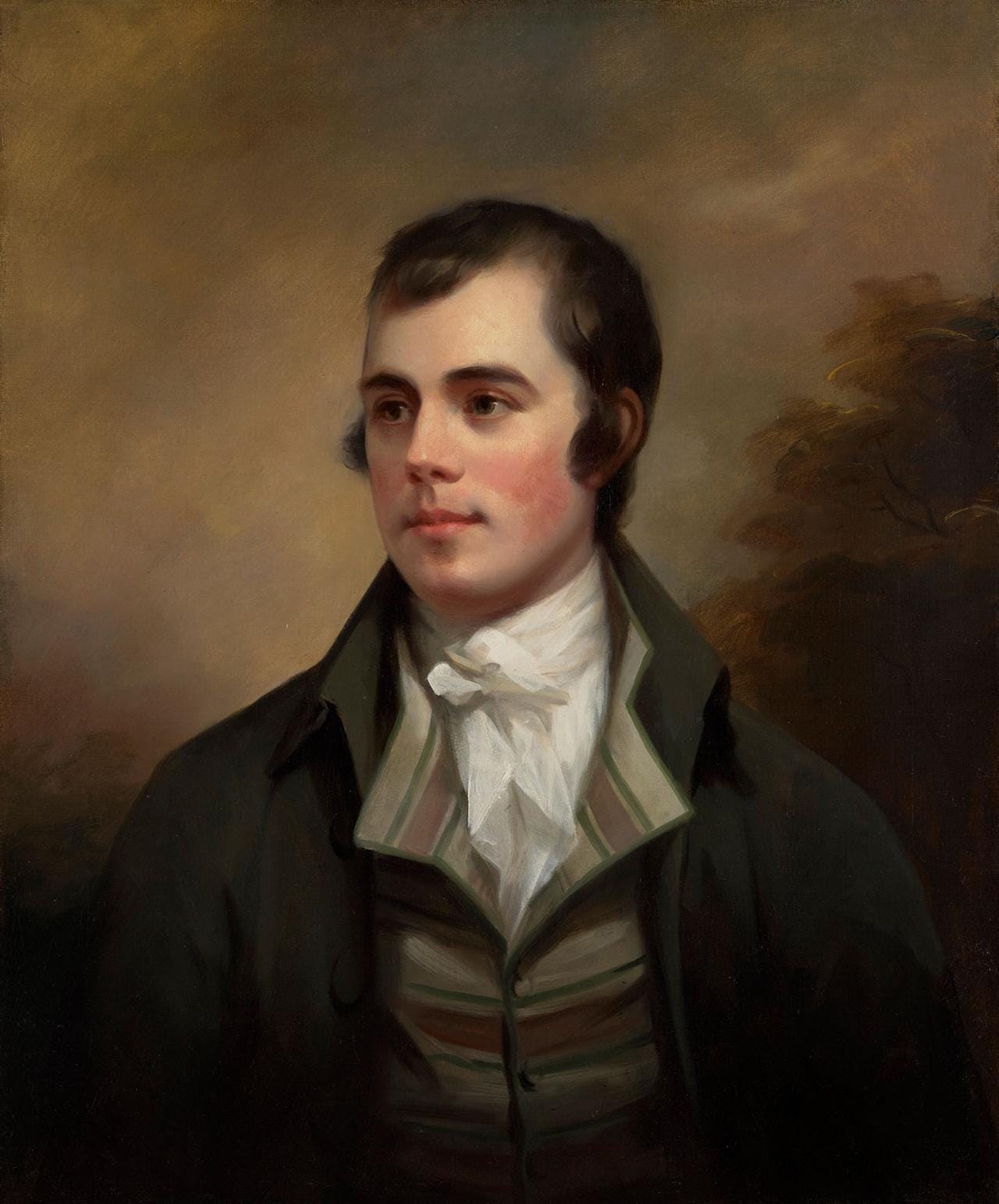

Don Paterson on the sudden disappearance of Robert Burns

Dry January has unfortunately resulted in some very dry North Sea poets, and the Substack cupboard was looking very bare this weekend. Just as well it’s free, eh? Subscribe below, if you haven’t! Burns Night, thank God, has ridden to the rescue. For many years I gave a version of the following lecture to undergraduate students at St Andrews on Burns, his Burns Supper warhorse ‘Tam O’Shanter’, and what it tells us about his abandonment of poetry for song. It also draws on an introduction I wrote for a little selection of Burns’ poetry I made for Faber back in the day. I thought I’d give the thing one final airing here before I finally put it out to pasture.

Burns was born in 1759 in Alloway in Ayrshire and died, neither very much later nor very much further away, in 1796 in Dumfries. He wrote his best poems in Scots, and his best poems were so good they did a great deal to guarantee the Scots language some kind of literary future. He suffered for his art, and lord knows others suffered for it too, particularly the women who loved him; but his art was also fuelled by his experience of suffering, especially that of watching his father beaten down by authority and exhausted by farm labour. While he became many other poets besides, this helped form Burns into a satirist of the kinds of religious and political thought that perpetuated or condoned inhumanity. And just as inhumanity has never gone out of fashion, neither has Robert Burns. What he made of us remains as true now as then.

Though one comedic aspect of Burns – maybe I mean tragicomic – is what we’ve made of him. Since his character was so complicated as to effectively not exist – there’s barely a single human trait that Burns did not exhibit at some point as if it defined him – everyone’s free to make their own reading of Burns according to their own personal, critical or neurotic agenda. And heaven knows they have. Burns is a everything from a noble savage to a brilliantly read autodidact; he’s a male-chauvinist pig, and he’s a champion of the rights of women; he’s a rather dodgy English late Augustan poet and a brilliant Scots proto-Romantic. Most bewilderingly from our contemporary perspective, the author of ‘A Slave’s Lament’ almost took a job at a Jamaican plantation as a ‘bookkeeper’ (which was ‘junior overseer’ in all but name). In view of all this, you should be aware that any single assessment of the Burns and his work will be one that many will disagree with. Folk tend to see themselves in Burns, even if it’s the self they most dread, and must condemn the most harshly.

I think it's a doomed project to attempt, as many have, to reconstruct Burns' character from his voluminous personal correspondence. Its volume is no guarantee of its trustworthiness. All that his letters confirm is that he was a shapeshifter; there’s no reason to believe he inhabited one character any less sincerely than he did another. But he wasn’t trying to be himself; I suspect self-identity got completely lost in the enterprise. In the language of more recent psychopathology, I might identify him as something of an ‘echoist’. (Where narcissists are everything to themselves, echoists are more of a list of missing persons.) Burns was a genius at fastening on the form of address best able to manipulate the emotions and affections of his interlocutor, through a brilliant mix of insight, impersonation and flattery, both concealed and unconcealed. His lift stopped at every floor from service basement to penthouse, and he would emerge conversing fluently in whatever tongue that put the company most at their ease.

But this was far more than mere ‘sleekitness’. It was achieved by his having organised his language, by a prodigious feat of the intellect, into a smooth continuum that ran from low Ayrshire Scots to high Johnsonian English. Burns' desire to be ‘all things to all men’ also gifted him the most remarkable linguistic resource that any Scottish poet has ever had at their disposal. For me, his tragedy is the extent to which that resource was partly squandered.

In Burns’ letters and conversation, for every triumph of eloquence and manipulation – and triumphs they were: of invective, wheedling, satire, silver-tongued seduction, hard-nosed business talk, prostration and self-abasement, editorship and man-to-man bawdry – there is always one hideous miscalculation, with Burns telling his correspondent either far more than they needed to hear or quite the last thing they wanted to. He was an ‘oversharer’: FYTMI – ‘For Your Too Much Information’ – seems to preface his every letter. He wrote brilliantly, but without much thought or revision. But here’s an odd contradiction: as a poet, Burns was at his best when he was most spontaneous. (Most poets are the opposite.) And as eloquent as he was in English, it was never Burns' native tongue; he had to think first, and that was generally fatal to results. All his best poetry was written in Scots. Though even there, I’d say that what has been too often admired - by Scots and non-Scots alike - is not his poetry but his revolutionary sloganeering: ‘A Man's A Man’, not ‘The Second Epistle to J. Lapraik’. It’s rousing stuff, but I don’t think it’s poetry of the first rank. But I sense there’s also something more profound to Burns' broad appeal.

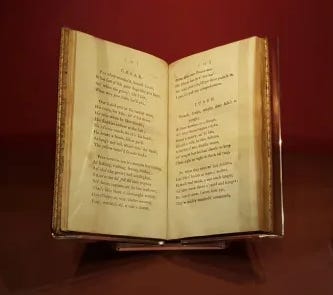

Most of the myths surrounding Burns are in a permanent state of recrudescence, so have to be dispatched annually. So let’s kick a few into touch. Yes, Burns received little formal schooling, and his knowledge of Scottish literature was confined, in his childhood, to the folk songs and tales of the oral culture. But he then read deeply in most of the important 18th-century English writers, as well as Shakespeare, Milton, and Dryden, and acquired a superficial reading knowledge of French. Burns was no ‘heaven-taught ploughman’ (as he was known to the posh Edinburgh folk whose patronage he later courted) but an intellectually brilliant and thoroughly well-read individual who could hold his own in the most sophisticated company. As usual, the error is partly Burns' own fault. He was cheerfully (and at the time, perhaps judiciously) complicit in the advertisement of his noble savagery: the preface to his first volume of poems – Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, the book we know as the Kilmarnock Edition – is, amongst a thousand other things, a notorious exercise in false humility. Burns didn't fish for compliments; he went after them with an elephant gun.

But I think his continuing appeal comes down to one important and starkly modern insight: people are an absolute mess. The spiritual, the social, the sexual, the natural, the comic and the political are coexisting human realms, not competing sensitivities that happen to be sharing the same organism. For all we may become adept at switching between them, all our various selves and their domains are not just collateral but often hopelessly mixed up: we tell jokes at funerals; we start political arguments on first dates; we experience sexual desire at the most inappropriate occasions. Yet literature often treats them as if there’s a rule that they must be strictly segregated, sometimes by genre. Burns felt that if you sang one, you should sing them all. One common result of all those colliding worlds and registers is human comedy - of absurdity, of self-contradiction, of hypocrisy. Comedy depends on the wrong thing happening in the right situation, or the right thing in the wrong one. Burns is terrific at showing us those clashes of personality and culture – not least as he was a such walking culture-clash himself. Burns doesn’t judge inconsistency: he knows it’s in human nature to be inconsistent. Burns instead destroys Holy Willie for his hypocrisy:

But yet O Lord! confess I must:

At times I'm fash'd wi' fleshly lust;

An' sometimes, too, in warldly trust,

Vile self gets in;

But Thou remembers we are dust,

Defiled wi' sin.

O Lord! yestreen, Thou kens, wi' Meg --

Thy pardon I sincerely beg --

O, may't ne'er be a living plague

To my dishonour!

An' I'll ne'er lift a lawless leg

Again upon her.

Besides, I farther maun avow --

Wi' Leezie's lass, three times, I trow --

But, Lord, that Friday I was fou,

When I cam near her,

Or else, Thou kens, Thy servant true

Wad never steer her.

(‘Fou’ is ‘drunk’; God is traditionally no more likely than the police to count this as a mitigating circumstance.) Burns' truest song is very simple, and it goes: Man is complicated. This insight was assisted by the fact that Burns himself was about as inconsistent a man as it is possible to be and remain halfway sane.

As I’ve mentioned, what also fuelled Burns’ tirades against hypocrisy was seeing his own father worn down – and finally out – by inhumane treatment at the hands of his creditors and the factors from whom he leased his farmland. Burns’ egalitarian ideals got him into trouble: he was excited by outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, and his vocal and indiscreet support nearly lost him his job as a tax collector. Only a humiliating public apology saved him. Though Burns did something of a nice line in humiliating public apologies, especially for his sexual misdemeanours; in those days, adulterers and fornicators would be obliged to make them before the whole church on a special high stool of repentance, the ‘cutty stool’. (‘Cutty’ means cut-down or ‘short’, but here it refers more to your docked pride and pruned reputation. Incidentally, Burns’ religious belief was tepid in the extreme, and about as enthusiastic as Shakespeare’s – but not attending the Kirk in those days simply wasn’t an option.)

‘Address To the Unco Guid’ is Burns’ most explicit exposition of his moral stance. Superficially, the poem might seem a hymn to moral relativity, and at one level no more than a retrospective defence of Burns' frankly comic inability to keep it in his breeks, spat back from the cutty stool that his arse was often warming. Burns, though, is hardly the first poet to find his greatest and fieriest eloquence in self-justification. The poem soon transcends its dubious occasion with its argument that the self-aware soul can act, in the end, only according to inscrutable interior mores, shaped by the unique patterns of pressure, attraction and resistance that form the weather of the individual mind. In this deeply serious poem Burns nonetheless finds time – of course he does – for scurrilous comedy, and just like the cracking mock-heroic epic of ‘Tam O’Shanter’, we get moments of high daftness:

Ye high, exalted, virtuous dames,

Tied up in godly laces,

Before ye gie poor Frailty names,

Suppose a change o' cases:

A dear-lov'd lad, convenience snug,

A treach'rous inclination--

But, let me whisper i' your lug,

Ye're aiblins nae temptation.

Ouch! It's also one of the few occasions where Burns successfully uses his full range. The poem's almost imperceptible stanza-by-stanza modulation from Scots to high English is a small miracle of rhetoric. The beautifully lyric lines ‘Then gently scan your brother man, / Still gentler sister woman; / Tho' they may gang a kennin wrang, / To step aside is human’ are the better known, but look at the enormous sophistication and intellectual brilliance of the final stanza:

Who made the heart, 'tis He alone

Decidedly can try us:

He knows each chord, its various tone,

Each spring, its various bias:

Then at the balance let's be mute,

We never can adjust it;

What's done we partly may compute,

But know not what's resisted.

Memorise that! It’s a superb verse to keep about your person. It also demonstrates what Burns had it in his grasp to achieve had he taken John Donne or Shakespeare as his exemplars; alas, he was more influenced by the likes of William Shenstone and Thomas Gray (he of the rather good ‘Elegy’ but precious little else). As is often the case with autodidacts, Burn was helplessly susceptible to influence. It was a bad age to carry this trait. His verse in English was destroyed, in part, by the example of those weaker poets (not forgetting such early bibles as Letters Moral and Entertaining by Mrs Elizabeth Rowe). Mercifully, Allan Ramsay – a poet who was central in reviving the interest in folk-song - and Robert Fergusson had a marvellous effect on his Scots. Fergusson, who was a student at St Andrews, died in an Edinburgh asylum at a very young age. He was brilliantly talented, hopelessly unstable, and in poems like ‘Braid Cloth’, ‘The Daft Days’ and ‘Auld Reekie’ – a terrific, witty and socially conscious portrait of Edinburgh – radiated an intellectual confidence that the Scots hadn’t seen since the medieval makars, in which vague grouping we include the likes of Henryson, Dunbar and Douglas. Fergusson had died both recently and young enough to allow Burns to indulge a deep identification; and Fergusson, like Burns, saw no contradiction in mixing serious and comic registers. It was a debt Burns often acknowledged, and Burns himself paid for a new stone to be erected over his grave in the Canongate cemetery in Edinburgh. (This totem for his ghost-brother was commissioned from - here, we can hear Jung chuckling in heaven - one Robert Burn.)

But otherwise, Burns was born in a very lean time for poetry. He was unlucky not to have been born twenty years later, when, with far more stimulating company and far better drugs, he would have made a fine Romantic. On the other hand, perhaps we should be grateful for what we got out of him: another fifty years down the road and he would have made a depressingly successful Victorian sentimentalist. ‘Sentimentalism’ is the art of professing to feel. What you profess to feel, and whether you may or may feel it at all, is secondary to the business of making a hymn to your own sensitivity. Practically all the poetry Burns wrote in English is thoroughly sentimental. Significantly, it’s not funny either; Burns didn’t associate his English register with humour of any kind. I’m not sure that you should bother to write in a language you don’t know how to crack a joke in. In Scots, though, he’s barely recognisable as the same poet. Burns is not, as some twerps persist in claiming, a ‘funny poet’; he’s merely capable of using humour the way we all use it, amid high seriousness, or grief, or drama. But if Burns the English poet were a violinist … Today, we would find him an intolerably syrupy performer, with a dreadful wide sob of a vibrato and not one phrase in his repertoire that we couldn’t immediately identify from another source. But in an insecure, mediocre or disenfranchised age (like the Scottish 1780s, with the enlightenment long behind it; or indeed today) the literate bourgeoisie are not looking to have their minds blown but their own mediocrity mirrored back to them, buffed and polished and tarted up. Add to that the novelty of his own lowly origins and his good looks, it was no wonder he took the drawing rooms of Edinburgh by storm – or that, fatally, so many encouraged him to persist with his weaker talents at the expense of his great gifts.

To those gifts: if I can stick with the musical metaphor - Burns may have been a second-rate violinist, but as a fiddler no one could touch him. With the discipline gained from his classical practice in English, Burns returned to the ‘rustic lyre’ of his Scots as a virtuoso the likes of which the instrument had never seen. Burns' slavish subscription to Augustan ideals of proper linguistic comportment may have been disastrous for his English verse, but it won his Scots a disciplined syntax, an intellectual ambition and a deep awareness of poetic artifice – as well as doubling his vocabulary at one stroke. Thrillingly, Burns now stood at a linguistic crossroads where Milton met Dunbar. This doubling of vocabulary is an important point: Burns' Scots is anything but pure - it's a sinewy, mongrel tongue always ready to import an English synonym, whether to raise the rhetorical stakes, or just to accommodate the local exigencies of metre and rhyme.

When he chose to ground this double tongue in Scots, Burns was less lowering the tone than levelling it, so that the lord's dog could talk to the ploughman's (see ‘The Twa Dugs’; this is a very ‘enlightenment’ ideal), and so he could prove that ideas can’t rely on the cultural authority of the language in which they happened to be couched, but have to stand on their own intrinsic merit. (Dialect, alas, still equals political voicelessness.) This is probably the moment for an important wee aside. Burns was a very smart guy - the chances are, a whole bunch smarter than you or me - who could have flayed you with his tongue in argument. Don’t let the lack of cultural authority that the Scots language currently enjoys deceive you into thinking otherwise. Don’t be Jeremy Paxman and call his poetry ‘doggerel’ because you’re culturally deaf to and therefore ignorant of its sophistication. Burns was good enough for Keats, Hazlitt and Wordsworth; he should be more than good enough for us.

Anyway: to the big question in Burns studies. Why did he just stop writing? I reckon that love was at the root of it. Burns was at heart a love poet, and all his satirical excursions were only possible while that principal conduit remained open. The dereliction of Burns' muse is no less strange and fascinating than that of Coleridge's or Rimbaud's. Coleridge lost his to idealist philosophy; Rimbaud lost his to a plain old disillusion. Burns lost his poetry to love. Which sounds odd, I know. I’ll explain the circumstances in a moment. But after the age of twenty-seven, he wrote very little poetry of any merit. The one exception is ‘Tam O'Shanter’. Tam O'Shanter’ is a late poem, written when Burns’ creative energy had been almost entirely directed towards song-making. It can also support – just as you would expect from its riven, strange creator – many different readings. But it’s usually recited, hysterically performed, or ritually murdered as a racy monologue at a Burns Supper.

Before we get into it, here’s a quick low-down on poetic interpretation. No one has the monopoly on what a poem means, and when anyone – whatever their professional or professorial status – tells you this is the definitive interpretation of a line of verse, they’re wrong. There can be none. Poems are unstable signs, written in a way that is deliberately ambiguous, equivocal, fuzzy, suggestive - and this way, everyone has the latitude to read something of themselves into the poem. Sure, some of our readings can be dumb. Some can be very smart. Some are very smart, and yet in no way licensed by the text, and largely the product of imaginative or ideological projection. On Jan 25th ‘Tam O' Shanter’ is subjected to its traditional narrow misreading and treated like a piece of stand-up comedy. I think a lot of the real significance of the poem is often missed. But it’s for you to decide if you find my reading a plausible one.

If we start by going along with Burns’ own conceit: ‘Tam O'Shanter’ tries to pass itself off as a semi-cautionary tale that warns of the dangers of drink, with enough winks and nods to the reader to suggest that there’s a little more to it. Its occasion appears to have been an invitation from the historian and folklorist Frances Grose to write an account of the legendary ‘Witches’ Meeting’ at Alloway Kirk for The Antiquities of Scotland (that the poem was commissioned, and not spontaneously written, is significant, I think). Burns, though, turned it to something very different. It is, I think, a whole bunch of bullshit that Tam delivers by way of explanation to his wife Kate, who’s understandably pissed off at him rolling in very late and very drunk with part of his horse missing. It can easily be read as a cock-and-bull story knocked together for her benefit, and is therefore a kind of dramatic monologue disguised by its third-person delivery, inside which this mad tale of witches is situated. What Grose will have made of this, lord knows. For poets, subject matter is mere pretext, and Burns has repurposed this bit of local folklore for his own ends. The poem is described as a ‘tale’, which one can read as a folktale, a story Tam has just made up, a story that Burns has just made up, a mare’s tail, or a ‘tall tale’. It’s a virtuosic entertainment, either way – one which works not just through its pace and comedy, but through its satire of literary genre. But regarding that satire … there’s a wee problem. Listen to this famous little pious aside:

But pleasures are like poppies spread,

You seize the flow'r, its bloom is shed;

Or like the snow falls in the river,

A moment white--then melts forever;

Or like the borealis race,

That flit ere you can point their place;

Or like the rainbow's lovely form

Evanishing amid the storm.

… This has been open to very various interpretation. Some read the passage as Burns dipping into his lame, didactic, high-pulpit Augustan English register; my money, given the context, is on irony – Tam is trying to give his story more credibility by adopting a silly, pompous tone that connotes I have learned my lesson and I am a wiser man. But there’s a problem here. If we accept that reading … The lines are just not as bad as they should be. They’re good. I read into this confusion of tone not only Burns’ ironised mickey-taking of sentimental English verse, extolling the virtues of temperance – but also genuine sadness at his failure to reach the Miltonic heights of which he was so nearly capable. He tries to throw something away, to write pastiche – and even that ends up far too good for mere parody. In the context of Burns’ career, I find these lines infinitely depressing.

Given that poets often use whatever off-the peg form that comes to hand, we can see Burns naturally reaching for the mock-heroic epic here – very much in the style of Pope’s ‘The Rape of the Lock’, a favourite of Burns’. Tam is a thoroughly unheroic, everyman figure, though – ‘Tam‘ will have been chosen for that reason, as in ‘Tom, Dick or Harry’. He’s just another drunken braggart, a Joe Blow spinner of yarns in which he plays the hero. But we sense he’s a bit of a joke to everyone else. While he pursues the usual Odyssean quest – to fight his way home through a thicket of adversity – the way in which he does so is comic and hapless. Did Tam remind Burns of anyone?

But where Pope’s poem is a stately and controlled affair, Burns’s poem is a wild ride. Burns is working in ‘low’, dialectal speech, and his characters are common folk; the tone of the poem is intimate, and it seems addressed the same constituency to which its characters belong. And it’s the more modern poem, not least because of the elements we might call proto-romantic: not just because it draws on the kind of rural and local materials we will soon see obsessing Wordsworth, so much as the the fact that this is clearly a ‘work of the imagination’, which enters a ‘nightmare’ universe, full of every Freudian motif in the book: unconscious desire, repression, suppression and sexual symbol.

But (as I confess I learned from my colleague at St Andrews, Professor Sara Lodge) we can also see the shape of a neoclassical poem in its symmetry, in the arc of its narrative. This is a midnight ride, so Tam’s journey is perfectly balanced between night and morning; we also have recurring motifs the ‘key-stane’ – both keystone of midnight, and the keystone of the Alloway bridge he must cross to be safe; we have the lovely balanced couplets of the poem’s form, and the kind of nod to classical simile that we heard in that ‘Pleasures are like poppies spread’ passage. But is the poem itself something of a symptomatic keystone, sitting as it does between the conscious, rational Augustan era of the enlightenment and the Romantic era of the imagination, dreams and the unconscious? The poem is both awake and asleep, for which ‘drunk’ is perhaps a decent analogue.

If we also remember Burns’ penchant for lengthy self-justification, Tam’s yarn certainly fits the psychological bill. But there are other aspects equally revealing of Burns’ psychology. From a technical point of view – I reckon the poem finishes about sixteen lines too early. Despite the fact the Burns knows he is writing as well as he ever has – his fundamental indifference towards its composition soon rises up and overwhelms him. ‘Tam’ was written when Burn was devoting all his energies to song, and I might read into this curtailed ending a literal enactment of his loss of faith in poetry. Perhaps it captures the moment when the mirror cleared.

Furthermore, the even more literal curtailment – the loss of his horse’s tail – is a detail that a Freudian might quickly interpret as vagina dentata, the male fear of emasculation. (Do see the movie Teeth, if you want to see this explored at hilarious and horrific length.) Burns was not consciously afraid of women, and nor was he anything like the misogynist some paint him (drawing on the tedious man-to-man bantz of the letters as evidence of this strikes me as profoundly naïve). But he did know that women – or rather his sexual desire for them - had completely exhausted his energy. The poem ends with the lines

Now, wha this tale o' truth shall read,

Ilk man and mother's son, take heed:

Whene'er to Drink you are inclin'd,

Or Cutty-sarks rin in your mind,

Think ye may buy the joys o'er dear;

Remember Tam o' Shanter's mare.

… Which we can, I think, fairly précis as ... remember what can happen to your tail – that little symbol of your artistic mojo – if you can’t control your sexual urges. So what prompted this insight? And did it precipitate the career-move from poet to songwriter? Some have seen Burns' switch to songwriting, collecting and ‘improving’ as a betrayal of his gift. Robert Louis Stevenson famously disparaged it as ‘whittling cherry-stones’. This is very unfair.

I still can’t help reading into Burns' feverish ‘womanising’ – though ‘shagging’ is by far the better and less sexist term, I feel – a terrible self-hatred. He tried to assuage it by proving that every woman loved him, but any course of action motivated by such a desperate feeling of lack can only end in its tragic reaffirmation. As A.L. Kennedy has pointed out, Burns, the man who more than anything else adored the company of women, would ultimately know that his presence in the room alone would be enough to blacken a woman's name.

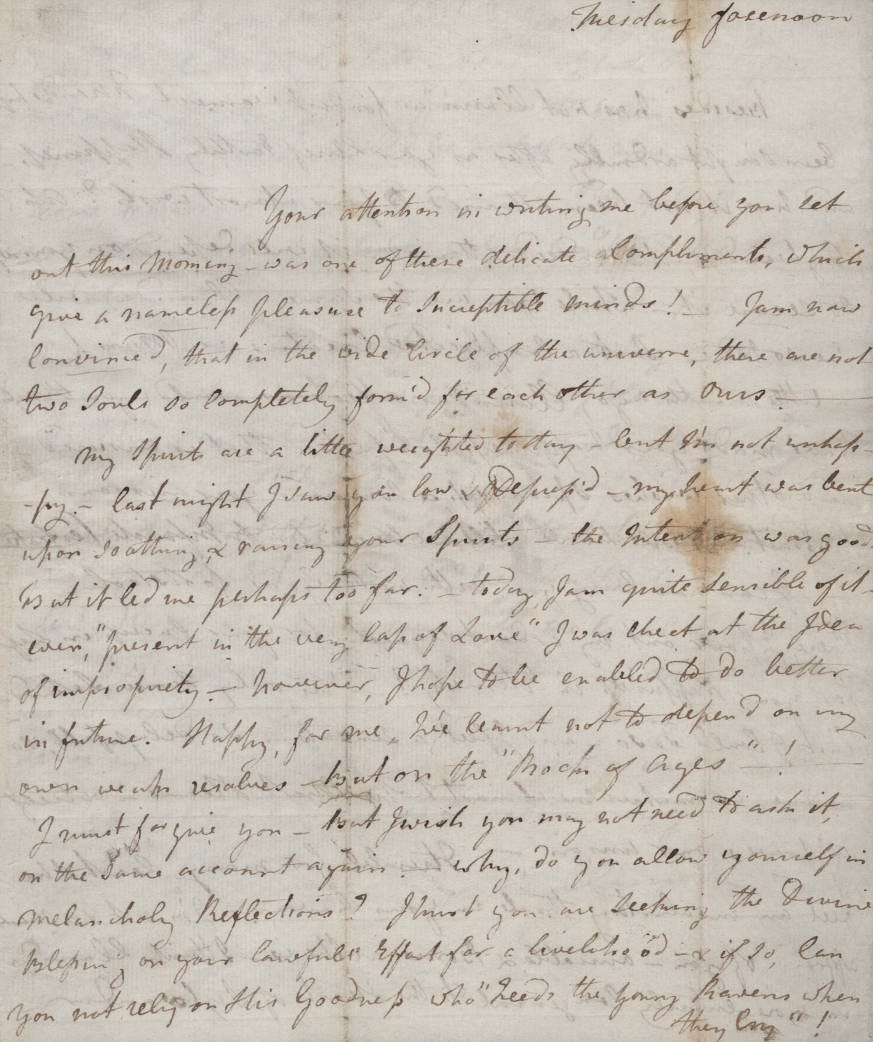

That hardwired internal connexion between love and poetry had probably been overloaded for some time, but one upper-class Edinburgh woman shorted it out for good: the brilliant, beautiful, and – alas! – sensibly chaste Nancy McLehose. Although Burns seemed resigned to the shapeshifting nature of his fickle muse (a relationship into which I read raging egotism and neurosis, not misogyny; Burns was forever guiltily picking up the tab for his amorous catastrophes and their consequent offspring), he still knew the dream-woman when he saw her. Burns' and Nancy's infamous epistolary exploits as ‘Sylvander and Clarinda’ have embarrassed and amused generations; but to dismiss them as merely so much affected neoclassical camp is to do a great disservice to a couple, clearly deeply in love, who were trying to bridge an impossible social gap. Nonetheless the results are still pretty funny, and affected as hell. But even for Burns, it stands out as a particularly desperate and moving performance, driven equally by an adolescent desire to impress, an intolerable sexual frustration and a deep and genuine emotion. It got him, in the end, nowhere. Imagine: to know yourself a better poet than almost any man alive, to have expended every ounce of your eloquent gift – and still come away empty-handed … This was a betrayal too far. In such circumstances a man has to curse someone, and as a natural self-hater – if the Kirk taught us nothing else, it’s who to blame - Burns really didn’t have to look further than his own shaving mirror.

By then Burns knew two things: that he was never going to find his intellectual equal in a woman of his own class (working-class women simply did not receive the education in those days), and that elsewhere, his low pedigree would forever count against him. He might be lionised in the clubs and an honoured guest at the dining-table, but elsewhere the caste system was as strongly enforced as ever. Burns was never quite Edinburgh’s dancing bear. But it was only a matter of time before a man of such simultaneously high and low self-regard would start to feel like one.

Burns' enthusiasm for his great song-collecting project had been earlier fired on a long tour of Scotland he made following a bad bout of post-Edinburgh tristesse. (His Scottish peregrinations may have also been an unconscious and slightly pathetic impersonation of the Grand Tour he was unable to afford. The likes of Johnson & Boswell’s Journey to the Western Isles had, however, ennobled the idea of the ’internal traveller’.) His allegiance to the poem – whatever his conscious mind was telling him – was probably already shaken. Poems, unlike songs, have an ulterior motive. If they didn't, they would just say what they meant and be done with it. After Nancy … There was nothing to be smuggled over the border, nothing to be breached, nothing to be won. Burns' love-poet skills, all his artful duplicities, were suddenly redundant. All that was left to him, if he was to go on singing at all, was to sing for its own sake.

‘Tam O’Shanter’ is really a late coda, detached from the body of his poetic work, and for all the comedy, all the satire .... There is a bitter regret in it, a regret, perhaps, for Burns’ own reckless excursion into alien territory, the magical world of the privileged class into which he was drawn by his ambition, both romantic and literary. In the end, it had only served to lead him dangerously far from home.

So home he went, to rural Scotland, to song, to the folk tradition, to Ayrshire, and to his wife, Jean Armour. Burns found a way of assuaging a now ruined, almost terminally fragmented personality by projecting it into a vast and partly anonymous project. It was, in a way, a very natural move; from trying to be all things to all men, it's a short step to being no one at all. Burn's revitalisation of Scottish song was so pervasive, its extent can never be fully known. It’s an abstract and mythic lovemaking where Burns' muse now wears the dress of nationhood:

Her mantle large, of greenish hue,

My gazing wonder chiefly drew:

Deep lights and shades, bold-mingling, threw

A lustre grand;

And seem'd, to my astonish'd view,

A well-known land.

Here, rivers in the sea were lost;

There, mountains to the skies were toss't:

Here, tumbling billows mark'd the coast,

With surging foam;

There, distant shone Art's lofty boast,

The lordly dome.

(from ‘A Vision’)

Back home in Ayrshire, Burns set up his lyric dockyard and spent his last ten years fitting out the old and dilapidated fleet of the Scottish traditional song-canon with fine new sails. The work was so skilfully executed that, two hundred years later, it’s still going strong. Burns’ work was so extensive and so pervasive, we have no idea of its extent. His interventions ranged from tidy upholstery to the creation of entirely new songs.

So there we go. It’s a feature of genius that it often completes its journey in its own mind long before it’s actually executed it. This anticipation can lead too easily to boredom, burnout, short-circuiting, impatient short-cuts and premature codas. For whatever reason, Burns was not the poet he should have been. But measuring how far he fell short of his own promise is no excuse for ignoring his real accomplishments.

Though in my bleaker moments … Sometimes I feel that not until the last Supper has been eaten and the Judas kiss of the last biographer planted on his bones will Burns be free of himself. (He’s had far too many. But if you read one life of Burns, I heartily recommend Robert Crawford’s superb The Bard.) As RLS remarked, Robert Burns died of being Robert Burns, and he’s continued to ever since. Those of us pleased to witness Scotland's growing political autonomy can reasonably hope this will change (future grumpy Don: not under this sodding incarnation of the SNP it won’t). Nations that fall short of actual nationhood have a far greater need for its fripperies. As George Bernard Shaw said, a healthy nation thinks no more of its nationhood than a healthy man of his bones. Perhaps when we can afford to forget ourselves, we’ll see the post of ‘national bard’ – along with the Nessie and the Gathering of the Clans – all go down the same plughole. Then we can get back to reading Burns’ best poems for the plain wonders so many of them are.

The spring ‘Writing With …’ courses are now both SOLD OUT … But please check the North Sea Poets website and the next newsletter for news of upcoming masterclasses, webinars and studios (we know we said that last time, but we’ll have some news very soon …) – and hit that subscribe button if you haven’t.

Our Substack is free, and subscribers receive advance notice of all events.

I'm no dry poet, sadly. Instead, I'll be raising a glass of Cutty Sark this evening to Mr. Burns and making my kids groan while I read a little Burns at the dinner table. Sláinte Mhath!

I did not expect to be saddened by an essay on Burns. Thank you for a great and thought-provoking read.