‘Here by effacement the poem is restored to unity’: The Genius of the Golden Treasury, part I

Don Paterson on the joy and misery of the anthology

Part I

I really wish I liked anthologies more. No: I wish I liked more anthologies. Asked the other day to recommend a few for someone new to poetry, I found I could only name books I’d filed under ‘works of pure enthusiasm’. The Rattle Bag; Jo Shapcott and Matthew Sweeney’s Emergency Kit; Ted Hughes’ Poems to Learn by Heart; Czeslaw Milosz’s A Book of Luminous Things; Paul Muldoon’s Book of Beasts; Robert Pinksy’s Essential Pleasures; a book I’d put together with Nick Laird, The Zoo of the New … All of them, books made of poems chosen for no other reason than their editors loved them. I found no room in my list for themed collections, or surveys of identities or age-groups or nationalities, or the forbidding overviews of Norton or Oxford. Had I been asked to suggest books for someone who wanted to educate themselves about poetry, that would have been a different matter, though even there I’d likely push them towards quite personal selections – like Edna Longley’s Bloodaxe Book of 20th Century Poetry From Britain and Ireland, say – that more neutral, ‘fairer’ accounts. Either way, I found I could recommend no books of poetry; only books of poems.

I thought it might be worth having a close look at the first modern anthology compiled on the principle of educated whim, not least because it remains the most successful of all time: Palgrave’s Golden Treasury of English Verse. It still reads as a work of pure enthusiasm. (ἐνθουσιασμός, to be inspired or ‘possessed by a god’, lest we lose sight of that.) As irrational, narrow, modish and strange as Palgrave’s passions were – as everyone’s are, surely – someone else’s personal enthusiasm is perhaps the only recommendation we can ever really trust, and perhaps the only kind that can be, as the cliché goes, genuinely infectious. Is there any other reason to publish an anthology?

Well, there are quite a few. I’ve done it, lord knows, and have acted as dutiful midwife to many a publication which sought to be fair and representative and inclusive and neutral and wide-ranging before it was … Brilliant. I can sleep, because the exercise was never cynical (ok; bar that one time), only pragmatic. I felt I left these books either as good as they were going to get or I could help make them, which was … Pretty good. They were all books that had a specific remit. And sometimes anthologies have served as symbolically important correctives, especially at times when broader changes to the publishing culture seemed impossible to effect: James Weldon Johnson’s The Book of American Negro Poetry or Florence Howe’s anthology of American women poets, No More Masks, for example. The School Bag was Heaney and Hughes sober counterbalance to the wilder private enthusiasms of The Rattle Bag. It’s not very exciting, but it’s essential. These were just poems on whose merit everyone had long agreed, if no longer with any great energy.

Other books compensate for smaller but still-glaring areas of neglect. Kathleen Jamie, Peter Mackay and I worked on The Golden Treasury of Scottish Verse because no such book had been made for eighty years. Between correcting for the long cultural omission and imitating Palgrave’s great passion project, we found we had to be both fair and partisan in our choices. It led to us, correctly, being neither wholly one nor the other, and we pursued a middle way. As scholars of the field, we probably fell short; as poets, we’d have chosen less widely and far more capriciously; but as editors, we were as pleased as editors can be with the result. Which is, y’know. Moderately pleased. I think it’s an anthology both pretty good and pretty useful in covering the territory and the timeframe; it's also the only one. But anthologies can’t be both brilliant and definitive.

The trouble is that the more dutiful a publication is, the fewer copies it will sell. Let me state that more boldly: the fewer people will want to read it. The Norton Anthologies sell well only because they make superb set texts, but readers generally don’t buy them. And that trendy thing that was devoted to solely to the work of poets from some very boutique intersectionality, and had you rolling your eyes at its po-faced self-absorption? Well cheer up, because that will have probably tanked too. All but the most naive publishers go in fear of anthologies, which are money pits. They cost a bomb, and they almost never sell. Just about the only way to make them work is to fill them with the copyright-free dead, pay the living next to nothing, and avoid the dead-but-still-in-copyright (otherwise known as ‘all the really great stuff’), insofar as you can bring yourself to.

Let me explain the basic economics of it. Feel free to skip the next two paras, as the ugly reality of the poetry-publishing economy can be a real downer. (TL;DR: most anthologies fail any basic cost/benefit analysis.) OK: suppose you have a great idea for an anthology. Everyone does from time to time. I do. You do. Let’s say you’ve put together your list of contents before approaching a publisher. I receive your pitch. It’s a thoughtful one: you’ve proposed a cracking list of poems. Let’s say that in Cheese Dreams: a Treasury of Dairy-Themed Verse – why on earth has no one thought of doing this before? – you plan to include about 200 poems, making around 300pp of poetry. Let’s say that half the poems in your list of contents are still in copyright. (That doesn't mean ‘are by living authors’, because you remain in copyright 70 years after your death in the UK, meaning you can easily be born in the 19th century and still owed permissions in 2025. Wallace Stevens is still raking it in.) This means 100 poems with average permissions fees of £100-200; so let’s say £150 quid a pop. It’ll be more, if the poetry list of a certain publisher is heavily involved. So we’re up to £15,000 already in permissions alone.

This outlay, from an accountancy standpoint, is the same as the ’advance against royalties’ an author or editor gets – which is why the editor will be now getting paid as close to zero as the publisher can get away with. Let’s say a generous (but pitiful, given the work involved) £3k. Now this £18k is not, of course, ‘the cost of the book’. The cost of the book is better thought of as proportion of the publisher’s total overheads. (There’s more to it, but … it’s ‘better thought of’.) The permissions + the advance are the debt the book has so far incurred, and which needs to be repaid. An author will see on average about 10% of the cover price; an editor, a good bit less. (1-3%, so that £3k will take much longer to pay back. Between you and me, it will never be, so you’re better taking it as a flat fee and forgetting the royalties. This way you don't owe the publisher anything.) But the other 90% will go to cover the huge costs of preparing, making, marketing, distributing and selling the book. Now suppose Cheese Dreams retails at twenty quid. To break even and clear its debt, it must recover 18k from that 10%-ish of the cover price. That’s only two quid per copy. So I’ll need to sell about 9000 copies of Cheese Dreams to break even. And that, in a nutshell, is why I’d never have commissioned it. I’d have had a look at a ‘comp title’, say Time Out: A Golden Treasury of Period Confectionary Verse that Bloomsbury did last year, and with no little Schadenfreude discover on Neilson Bookscan that only 237 copies had been sold. Which means that Bloomsbury lost all their permissions money, all the editor’s advance, and published a heavily loss-making title.

I might then think about giving you a second option. How about we make the whole thing 80% out-of-copyright, cut your fee to 500 quid, reduce the book to 100pp, ask that you go and beg the handful of living poets to give you that great Camembert or Brie poem of theirs for nothing, tell you to forget about almost everyone who died after 1955 (especially Plath, Eliot and most famous yanks; though I know the loss of your centrepiece, Plath’s ‘Moon Wedge Love Song’, the one about Dairylea slices, will hit you hard), and convince Simon Armitage to write a two-para foreword so we can get his name on the cover. Only I wouldn’t. I don't believe in you working for nothing, or poets not getting paid. And Simon will get ten such requests a week. And the book will now be a bit rubbish. So I’d pass instead, with genuine regret.

And that’s the reason there are very few successful anthologies: the sums don’t work. Though a few anticipate their academic and commercial markets in a much smarter way. In the popular market, the self-help/feelz books can really cut through, if it’s well pitched - Poems to Make Your Dad Cry and The Poetry Homeopath and Haikus for the Heart, all that stuff. These books will often sneak in good poems among the dross. Back in the day, I particularly admired the success of Neil Astley’s Bloodaxe anthology Staying Alive: Real Poems for Unreal Times. It was not just a brilliant piece of marketing, with Astley ingeniously riding the second wave of the self-help boom; it was also a sincere attempt to sell poetry as a salve to the wounded soul. Readers can smell an insincere book. As a brilliant piece of publishing which helped poetry reached a huge new audience, it’s without recent parallel, despite its being eked out with many Bloodaxe poets to more affordably fill the ‘contemporary’ quota. (A stronger feature of its hastily compiled sequels, which suffered a result. Would I have done any differently as a publisher? Hell no.) Yes, it’s a imperfect book, because it's a genius of compromise. But it was still a big risk. There will have been considerable financial outlay. But Neil found a way to make it work, and while all those celebrity endorsements may have had many of us groaning at the time, they brought the work of many good poets to the wider public consciousness.

(You will never please everyone, and you must not try. I had complaints that The Zoo of the New both contained far too little recent poetry and far too much. I was collared by someone who accused me of something I hadn’t heard before, the crime of ‘deadism’ – that is to say, we had unfairly overlooked too many of the existentially challenged and had shown too much favouritism towards the breathing. I replied that I have nothing against the dead, and that some of my best friends are dead. My own most anthologised poem, for the record, is called ‘On Going to Meet a Zen Master in the Kyushu Mountains and Not Finding Him’, and is completely blank. It is also my cheapest poem. I don’t think the two points are unrelated, any more than it was a coincidence when, a few decades back, the New Yorker changed its poetry fees from a word-rate to a line-rate. Overnight, US poets all suddenly discovered an intense fondness for the two-stress line.)

But let’s go right back to Francis Palgrave, he of the million copies sold and counting – we don’t have exact figures, but he was sitting at 700k by 1939 – and look at what he got right. Everything starts with a trip to Wikipedia, though as several hungover academics have learned to their terrible cost, it should not end there, especially if the student has their laptop open to the same page during the lecture. But as far as Francis P. himself is concerned, I discover only that of which I am already broadly apprised, which is that ‘his principal contribution to the development of literary taste was contained in his Golden Treasury of English Songs and Lyrics (1861), an anthology of the best poetry in the language constructed upon a plan sound and spacious, and followed out with a delicacy of feeling which could scarcely be surpassed.’ Amen to that. Though much in the way that a piece of student plagiarism or AI involvement can be detected by the presence of a well-placed semicolon, there is something, is there not, in the old-world elegance of that phrasing, something in its less-than-perfect forensic objectivity, that makes one suspect this assessment of Palgrave’s merit may not be wholly contemporary. I’m pretty sure it’s a cut-and-paste job from a long-dead author, though I choose instead to believe it was typed out with two gnarly fingers on the last still-working Amstrad by some desiccated nonagenarian Oxford don as he enjoyed a glass of madeira and a cold collation in his dusty, sunless rooms. It feels entirely of a piece with the Treasury. Palgrave’s wiki, in its lovely Victorian comportment and shameless bias, makes me nostalgic for a time and indeed an ‘England’ when such casually elegant writing was the default, when such windswept confessions of taste were not just tolerated but encouraged, and when scholarship in the humanities was free from any obligation to present itself as fake science. But we’ll have to dig a little deeper.

The anthology itself is a very old idea. I’m sure you’ll all know the word’s etymology from the Greek anthos, flower, + logia / legein, to speak or to collect. So: a collection of flowers. We can partly trace the word to a very early collection of epigrams, Στέφανος, ‘The Garland’, from Meleager of Gadara in the first century BCE. Small poems had forever been compared to small flowers, and Meleager attached the names of flowers and herbs to the poets he included. The Garland was one of the principal sources of what became The Greek Anthology, whose name was a nod to Meleager’s earlier work. After that, it was more widely applied to any collection of poems by many different hands. It’s the word ‘anthology’ that Wavell – Field Marshall Archibald Wavell, Viceroy of India – puns on in the title of Other Men’s Flowers, which, for a while, was the Treasury’s commercial competition from Macmillan’s big poetry rival, Jonathan Cape. The Treasury won, both on sales and longevity: the Golden Treasury is also the better name, and the better book. (You get the sense a few too many of Wavell’s poems were memorised under sufferance for Recita at Winchester College as a form of weekly torture, and not solely for his own delight.)

But there have been thousands of anthologies. Why would one make such a book? Well, let’s think about what it does, or what it used to do. First of all, an anthology boldly declares that the poems in it are better than other poems – though rarely as openly as Palgrave’s does. This also claims an expertise for its editor. Secondly, it declares the primacy of the poem over the poet. This is the big difference between true anthologies like the Treasury, and likes of The Norton Anthology, which – wonderfully useful as it is – is not an anthology but a survey publication. Thirdly, it removes the poem from the context of its original sequence or book or oeuvre; a Shakespeare sonnet, say, is liberated from the narrow narrative of his love affair, and while it might not ‘gain’ as a result, its resonating into the more democratic space of the anthology means we can make it more personally relevant, and free to read more of ourselves into it. Fourthly, anthologies also allow those who have written only one great poem – in the Treasury, W.J. Mickle’s lovely Scots song, ‘The Sailor’s Wife’, say – to see it win the exalted place it deserves. (Silver and even bronze poets can produce the odd golden poem, and still do.)

Lastly, it does that thing that blokes, especially, love: it forms a canon, i.e. a class based on a principle of exclusion. Nothing wrong with that, except that they can be quickly shaped into hierarchies that allow folk to indulge excitable notions of top dogs and also-rans, and of patriarchal, dynastic or Oedipal succession. (See, for example, Auden’s higher status in the US, which is partly a product of his being too heavily represented in anthologies at McNeice’s expense; or Bloom’s increasingly mad ideas around the ’anxiety of influence’, which the canon he promoted then served - circularly - to underwrite.)

But far more importantly, anthologies liberate the reader. They allow the reader a sense of serendipitous discovery, of personal encounter, with the usual intermediaries removed – the poet, the critic, the literary conventions of reading. It’s just them, and a big book of magic spells. The anthology reminds readers what a poem is. While Palgrave might intend his book to be read in sequence, anthologies really encourage us to indulge Randall Jarrell’s favourite warcry, Read at whim! Most of us love the idea that we can open a book anywhere, and – almost in an act of bibliomancy – find a poem that miraculously seem to speak to us, right here, right now. To this day, I find something magical about great anthologies: The Rattle Bag was, for me, the kind of wonderful cornucopia the Treasury was for Victorian readers. But I want an anthology that feels like a commonplace book, where everything was copied out by hand, or learned by heart for no other reason but love. If you love something, it stores that love, and it can fire it in others. This is very much the kind of book Palgrave made, and he never conceived of any other.

In Monday’s part II, I’ll look at what it was, exactly, that Palgrave got so triumphantly right.

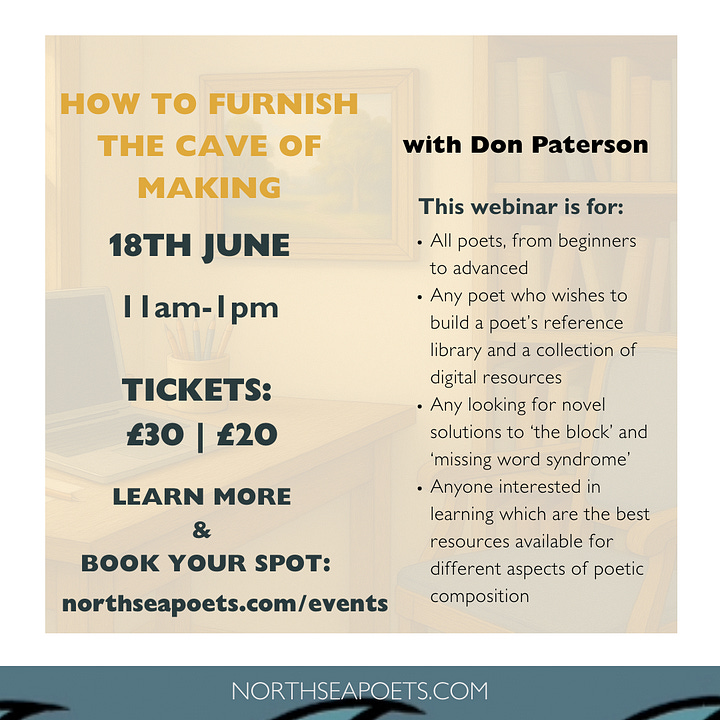

Don Paterson’s next event, How to Furnish the Cave of Making, is coming up on 18th June. Get all the details at northseapoets.com 🌊

Thank you for this. Made me laugh out loud. Glad to see a shout out for Neil Astley. In my youth the Quiller-Couch was canonical so have had to spend a life-time freeing myself from it. I think I like collections - The Imagists, The Mersey Sound - but reflections on the word ‘collection’ perhaps won’t lead to the same level of richness you find in the etymology of ‘anthology’. Looking forward to Part the Second…

This is great; looking forward to Part II.

Shout out to 'I Like This Poem' (Penguin, 1981), which came with the added bonus of italicised endorsements by children at the end of each poem. It was instructive and weirdly dizzying as a child to realise that reading a poem and then HAVING AN OPINION on that poem was an Actual Thing.