Each Nick and Scratch by Heart: Elizabeth Bishop’s Island Industries

Lisa Brockwell on the perversity of nostalgia

I’ve been thinking about Elizabeth Bishop’s “Crusoe in England” for many years. It’s a strange poem: ostensibly a dramatic monologue in the voice of Robinson Crusoe, back in England, reflecting on how he survived solitary island life. Full of anachronisms and dreamlike tangents, it’s clear Bishop is not trying to truthfully inhabit Crusoe, but rather the archetype of the Crusoe figure: the castaway who builds a new world from available materials and is utterly self-reliant. What does this do to a person? The poem explores such a particular and profound contrast of human destinies. Some people are marooned or exiled, and rely solely upon themselves in a strange land; others live their entire lives within a family and never leave their hometown. Which would be the more representative, or more true, of human experience, if one had undergone both?

‘Crusoe in England’ was first published in The New Yorker on May 6, 1972, and later included in Bishop’s 1976 collection Geography III. The title of that final collection is important: Bishop was concerned with mapping the human imagination and the distance we cover in our lives, both physically and psychically. It’s there in the titles of her other collections too, North & South, A Cold Spring and Questions of Travel: books which chart questions of experience, belonging and exile, homecoming. Geography is the science of the surface of the earth, its naming and navigation. Typically, ‘Crusoe in England’ had been in gestation for many years. Bishop refers to drafts in letters written in the mid-sixties, and reflects on Crusoe in notebooks earlier still. Way back in 1934, she visited a friend on Cuttyhunk Island off the coast of Massachusetts, writing:

You live all the time in this Robinson Crusoe atmosphere, making this do for that, and contriving and inventing.

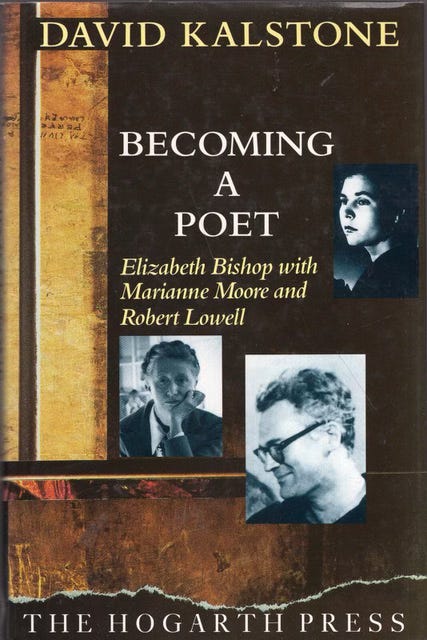

David Kalstone’s Becoming a Poet is a brilliant and thoughtful biographical study of Bishop’s work told through the frame of her friendships with Marianne Moore and Robert Lowell. He suggests that the poem is a form of ars poetica:

The constellation is striking: the strangeness; the practicality of Crusoe; the moral strenuousness linking ingenuity, courage and loneliness. It suggests how fortunately, for a few years, Bishop’s active and fantasy and writing lives were fused.

This fusion took place while Bishop was living in Brazil. There she began writing ‘Crusoe’, but finished it back in the US, where she was working at Harvard following the death of her partner Lota de Macedo Soares in New York in 1967. The description of Crusoe’s relationship with Friday feels ambiguous and apocryphal. I’m left with the sense of a partial glimpse into someone else’s marriage, but I’m not sure if what I’m seeing is just a very well-rehearsed version of close-up magic or candid, fly-on-the-wall access. The poem ends with a terrible, simple irony – the loneliness Crusoe has endured since his return to England:

–And Friday, my dear Friday, died of measles

seventeen years ago come March.

The structure and length of the poem showcase two key elements of Bishop’s style: precision and patience. It’s a long poem with subtle, varied music. No line is throwaway; no line appears which hasn’t been tested and weighed meticulously. And yet nothing feels overcooked. The sounds are naturally variegated, and the line- and stanza-lengths fall like natural speech. Crusoe prevaricates, changes the subject, and the lines switch between almost-empty phatic exchange and symbolically charged content. This confident pacing and confiding, indiscreet tone creates imaginative space in the poem, making room for the reader – one of Bishop’s hallmarks. Like Frost, she has mastered the art of using the sound and rhythm of phatic language – the speech we throw in purely to enhance and facilitate social relationships – to create a resting or listening space within the poem, a space that gives the reader the opportunity to enter, and to create meaning. This patience and confidence is often confused with ideas of feminine restraint and quietness by some male critics. I’m always surprised when these critics misinterpret her technique as feminine delicacy or reserve, I see it as much more wily and daring: the use of unpoetic, vulnerable language in a medium where we are always being told that “every word counts.” In this case it’s a way of humanising the castaway archetype and emphasising his social isolation. But just as Robert Lowell was wont to do in his letters, too many men are quick to project a ‘Madonna’ archetype onto Elizabeth Bishop. (Hmm: quite a big topic; maybe we should host a North Sea Poets workshop on gendered readings of women poets? Stay tuned!)

Within this conversational mode, Crusoe’s stories and recollections can meander; he describes his dreams and hallucinations on the island as almost fractal, as an endless splintering of the self:

… I’d have nightmares of other islands

stretching away from mine, infinities

of islands, islands spawning islands,

like frogs’ eggs turning into polliwogs

of islands, knowing that I had to live

on each and every one, eventually,

for ages, registering their flora,

their fauna, their geography.

Like the islands in ‘North Haven’, her elegy for Robert Lowell, Crusoe’s islands are as changeable as people: they are born, they die, and they alter as they travel through time and space. Birth and death haunt the poem in other unexpected ways too: Crusoe dyes a baby goat red to alleviate his boredom, but it is then shunned by its mother. He dreams of slitting the throat of a baby, mistaking it for one of the goat-kids he must kill to survive. Friday takes to carrying a kid around the island like a baby; Crusoe wishes Friday had been a woman, so that they might have had a child together.

The poem maps the geography of solitude and the imagination in extremis. It shows the creation of the tools – both literal and internal – needed to survive such an experience. And just what happens to this self when it is rescued, and able to go ‘home’?

The knife there on the shelf—

it reeked of meaning, like a crucifix.

It lived. How many years did I

beg it, implore it, not to break?

I knew each nick and scratch by heart,

the bluish blade, the broken tip,

the lines of wood grain on the handle ...

Now it won't look at me at all.

Why do I keep coming back to this poem? When I was a young girl, stuck in a troubled home and longing to be old enough to escape it, I often got myself to sleep by imagining life on an island. I would have to organise a new society. I’d set teams to work on building, farming, taming and looking after animals, storing and cooking food. God only knows why I was in charge. Granted, I was a bossy girl, but I had zero expertise in anything practical. That’s still the case. But as fantasy, I found it deeply comforting. Building a world and setting things to rights. Setting up home. I was a teenager in the 80s, that generation terrified of a nuclear apocalypse, and obsessed with safe havens; I guess if I’d been a child of a later generation I would have escaped into The Sims.

This is the terrain – the real cost of self-sufficiency – Crusoe explores, and probably one of the reasons I keep coming back to it. The archetype of the castaway is universal, and literature has been preoccupied with questions of travel, separation, home and survival since the Odyssey. It’s unusual, though to read a poem that so succinctly and honestly captures the perversity of nostalgia and longing. In exile Crusoe longs for home; once back in England, he longs for his island, or, at least invests it with more nostalgia than it seems to deserve. As an Australian who has ended up at home in Scotland, I understand that contradiction well, and it’s a relief to see it honestly rendered in such a fine and subtle poem.

Like Crusoe’s charmed knife, Bishop’s poems are the opposite of disposable and single-use; they are designed to be held close, memorised, and contemplated for as long as we have. We can always find our space within them.

John Glenday’s first event, A Weather Eye, is on 15th July.

Don Paterson’s next event, The Rhyme of Things: a new approach to metaphor, is coming up on 26th July.

Get all the details at northseapoets.com 🌊

A lovely insightful essay that captures the skill, vision and generosity of Elizabeth Bishop's poetry. Your remarks about how she opened 'a space that gives the reader the opportunity to enter, and to create meaning' reminds me of that marvelous 'space' in the 'The Moose' when the speaker, on behalf of all the passengers of the Boston-bound bus (as well as all the poem's readers), says

In the creakings and noises,

an old conversation

- not concerning us,

but recognizable, somewhere,

back in the bus:

Grandparents' voices

uninterruptedly

talking, in Eternity

What other poet could have used such an unpromising word as 'uninterruptedly' so well? What other poet has had the selflessness to use the second person plural so poignantly?

Many thanks for such a thoughtful scrutiny of the poem. Interesting to think about gendered readings in relation to this poem and a certain famous island poem by John Donne…?