Burn Your Notebooks

Lisa Brockwell on Elizabeth Bishop and the dangers of leaving it all too late

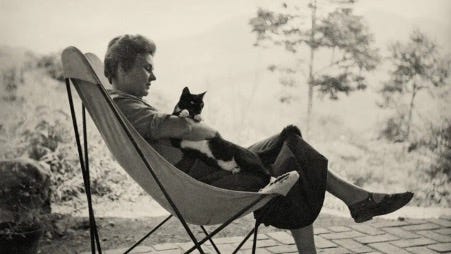

When Elizabeth Bishop sat down on her bed to put on her shoes on the 6th October 1979, she was preparing to go out for dinner and due to be picked up within the hour. She certainly wasn’t expecting to have a cerebral aneurysm and die. She was only sixty-eight.

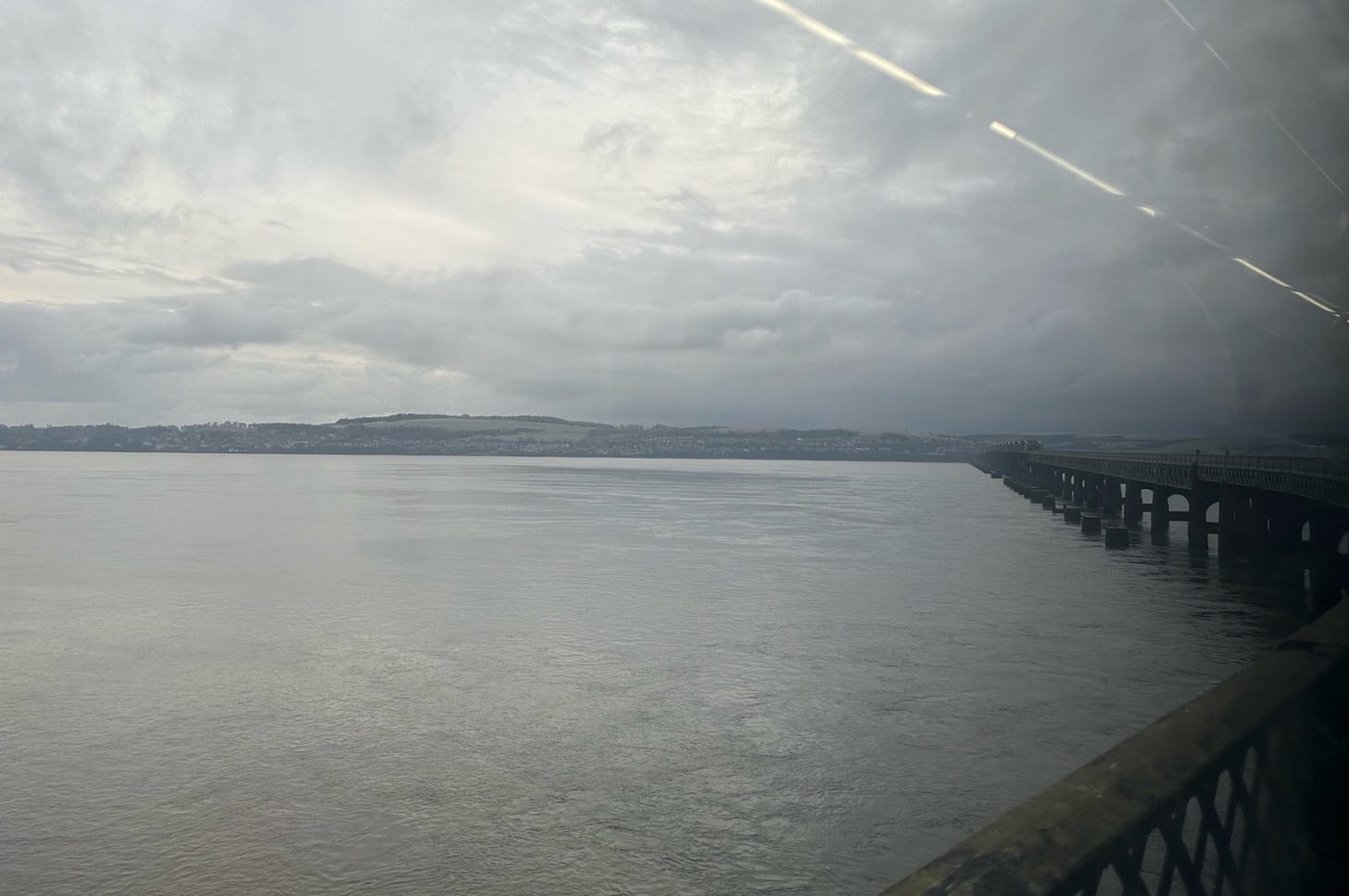

If her death hadn’t come so early and so suddenly, I very much doubt that Edgar Allen Poe & the Juke Box, Alice Quinn’s controversial book of Bishop’s uncollected poems, drafts and fragments, would have seen the light of day. The book is entirely out of step with Bishop’s meticulous quality control: Bishop published only 101 poems and translations in her lifetime. I feel miserable that her legacy has been forced to carry this book of failed poems, private fragments and early drafts that go nowhere. Although the book was published twenty years ago, I’m writing about it now because I only read it for the first time while preparing my recent North Sea Poets class on Bishop. I’d known of its existence, but had been – wisely, it turns out – avoiding it. And I can’t believe there wasn’t more sustained outrage on her behalf.

At least there was some. At the time, Helen Vendler, in a scathing review in The New Republic, called it a book of ‘repudiated’ poems. I would argue that they aren’t poems at all. The most charitable interpretation is ‘raw material’: ideas that didn’t work or go anywhere, and were rightly abandoned. A poem isn’t a poem until it’s ready to make its own way in the world as a finished, polished piece of art; its publication represents its formal gift to the reader. Before then, it’s the – often very – private property of the poet in whose notebook it took root and grew (and indeed often died). Surely this rule especially applies to Bishop, a poet not only with a track record of award-winning books, but also famous for her astonishing rigour – someone who could wait for years to find the right word or phrase, and finally deem a poem ready for publication. Bishop is the opposite of a freewheeling, stream-of-consciousness writer; there is something even more violating and upsetting not just in seeing her process on display, but in the false claims for its ‘finishedness’ made to justify the act. Increasingly it feels to me like an act of vandalism.

Some would argue that this privileging of the author’s intentions perpetuates a romantic point of view that gives the artist too much power. Poststructuralist theory would say that since the author is dead – mega-yawn – and since all texts circulate in the free market of global discourse, none should be privileged above others; a book of fragments and drafts has as much legitimacy as a book of finished poems endorsed by the author.

I don’t believe any of this, and neither does posterity. It’s a profoundly anti-art take on the human creation of meaning. Poems become part of our culture when they are excellent: when the author has endeavoured to say something new, and impeccably so – and when readers slowly recognise and agree that this has happened, committing these poems to memory, reading them at funerals and weddings, carrying copies in their wallets. The poet comes to be a trusted brand, a byword for great poems. A book of fragments, early drafts and things pulled from the wastepaper basket might not necessarily diminish that reputation, depending on the context in which they’re brought to light – archival research, academic monograph and so on. But to pass them off as something close to a book of newly discovered poems?

If we need evidence of how Bishop gained her reputation as one of the twentieth century’s most careful and meticulous writers, here she is in an interview the year before her death. When asked how long it takes her to write and finish a poem, she replies:

“From 10 minutes to 40 years. One of the few good qualities I think I have as a poet is patience. I have endless patience. Sometimes I feel I should be angry at myself for being willing to wait 20 years for a poem to get finished, but I don’t think a good poet can afford to be in a rush.”

Edgar Allen Poe & the Juke Box tells us that her editors and publishers were, in fact, angry at Bishop for being so patient and scrupulous. In her introduction Alice Quinn writes, “Early on, editors understood her perfectionism and regularly tried to goad her to let go and send them her poems.”

Unsuccessful in their attempts to badger and winkle and prise further material out of Bishop during her lifetime, it seems the literary machine was ready to punish her once she was no longer around. ‘Unconscious revenge’ is a hard thought to set aside, here. As well as being perfectionist in her work, Bishop was also profoundly discreet and unforthcoming about her personal life and her unhappy childhood. She despised the confessional mode in art and life, and would not be publicly drawn on the terrible losses she had endured. Her poems are so powerful precisely because they channel this deep feeling through the symbolic realm, and readers can recognise their own loves, joys and grief in the work. Bishop transmutes her own experience into the human universal through not just her skill and her talent, but her reserve.

For Bishop, this was a slow, erudite, alchemical process. The power and confidence of her work comes from the poet taking a step back and letting her poetic subject – animal, landscape or place – step forward. Her patience allowed her poems to reveal themselves, the edges of their domain to become clear, their symbols to become solid and to shine. Her immense and subtle talent depended upon this patient unfolding. The process could not be simply sped up; the poem could not be made to order. Apparently, this was a method her editors and publishers neither understood, respected nor sympathised with.

For this reason, many of the fragments and drafts published in Quinn’s book are not recognisably written by Bishop. They have not experienced the full process of slow heat and continuous year-on-year pressure that leads to the crystallization of a ‘genuine’, finely-honed and worked Bishop poem. Many are raw, sentimental outpourings of feeling, or clumsy metaphorical takes. They read as early notes, diary entries, things written in the heat of the moment, written when ill, or written not entirely sober. They sound like generic private notebooks. They sound like … us. I don’t feel comfortable quoting from it. I’d be committing the same intrusion on Bishop’s privacy as her editors and publishers.

Every writer has these private journals. I found one of my own while cleaning out some drawers over the Christmas break, one from a particularly painful and tumultuous time of my life. Even now, years later, I couldn’t bear to read the entries – they’re still so raw, and now also so embarrassing. But I won’t throw the notebook out. I know that one day I might go back to it, and find a talisman or a symbol or an episode in there I can use. But to have kept that notebook in the first place – to have that reservoir of my life experience later available for my work – I had to trust that nobody else in the world was ever going to read it. I find myself furious that Bishop was not afforded this basic respect and dignity. I’m sorry that she didn’t have the foresight to make better provision in her will, and I’m sorry that her next-of-kin and literary executor did not act with her best interests at heart. I don’t want to speculate on the motivations or possibly just the dereliction of her executor, her ex-partner Alice Methfessel; that also feels prurient and intrusive. I can certainly speculate on the motives of the editor, the publisher, and The New Yorker and other magazines that chose to publish these “poems” in a commercial market. Some will be purer than others, and some more complex than others. I’d merely argue that they all reached the wrong decision.

But I also want to understand. This project was obviously a labour of love for Alice Quinn. Her admiration for Bishop’s work is clear. So what motivated her? How could she believe this book was burnishing rather than tarnishing Bishop’s legacy? Quinn has written 120 pages of detailed annotations on these fragments. Some of the notes are undeniably interesting, but it seems absurd to spend so much scholarly effort and time on private scraps never meant to see the light of day. It strikes me as a rather circular and possibly passive-aggressive justification for the intrusion: ‘Look how important Bishop’s private papers are! If I’m finding so much in them of such obvious interest to readers, how can anyone think they shouldn’t be published?’ It’s a moot argument, and with a dead person who obviously didn’t make any sensible provision for their literary estate, but it’s an argument Quinn seems to be having. In this way the book feels pre-emptively defensive. She rather hides behind being “asked” to compile the book for FSG by Robert Giroux, who died, at the age of 95, two years after it was published.

And while we’re here – why on earth doesn’t a scholarly, fully annotated version of Bishop’s Complete Poems exist? For poets, certainly, Bishop is just as important to the canon as Eliot, Yeats, MacNeice, Moore, Frost – and now, Heaney. Did Quinn really want to edit and annotate the published poems, and find herself prevented from doing so? Perhaps the permission fees would have made such a project ruinously expensive.

The marketing of the book was especially revealing. Elizabeth Bishop’s name is in huge lettering across the top of the cover, as though heralding a new and undiscovered book of poems, as if she was … The author. Worse, many of these half-finished or wholly abandoned pieces were trailed as new poems in top-tier literary journals and magazines – including The New Yorker, where Bishop had a first refusal contract for many years. And I have to mention the meretricious and frankly fraudulent title: does Edgar Allen Poe and the Juke-Box sound like the title of a real Bishop poem or collection of poems to you? Her titles are spacious, confident, neutral. This one is straining, overworked and completely out of character.

In her review of these “maimed and stunted” drafts, Helen Vendler focuses on the publication of a fragment called ‘Washington as a Surveyor’ published in The New Yorker with no explanatory note, as though it was a newly discovered poem. The fragment was taken from a private notebook from 1934-36, when Bishop was in her twenties.

“There is something reprehensible in printing this feeble item in The New Yorker and signing it “Elizabeth Bishop”, especially when the poem is listed (in Quinn’s “A Note on the Text”) as one of the “Drafts Included That Were Entirely Crossed Out by Bishop in Her Notebooks and Papers”. Maybe it should have been printed in The New Yorker entirely crossed out.”

Indeed. Surely a fragment consisting solely of a few lines in a private notebook vigorously and ‘entirely crossed out’ does not, in fact, constitute a poem? Isn’t this ‘poem’, in fact, a posthumous fabrication? Surely all reasonable readers can agree on that?

(A side note: Helen Vendler’s 2006 review is so negative and fierce one almost suspects it of being suppressed. It’s now impossible to find online, bar one obscure internet archive. Many reviews cite Vendler’s piece, and The New Republic carries subsequent discussion, but the review itself has disappeared.)

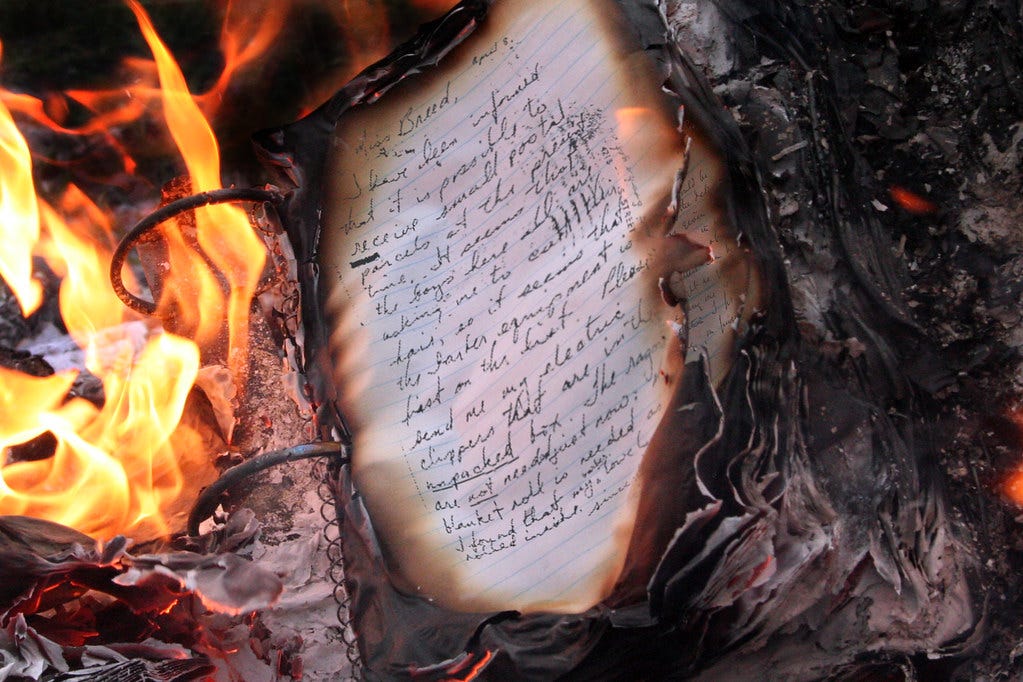

Vendler says that several poets of her acquaintance burned their notebooks after Quinn’s book was published, and I have every sympathy. She also cites the example of Gerard Manley Hopkins, who asked his sisters to burn his spiritual notebooks after his death, and I’m glad they did. I love Hopkin’s poems and published notebooks, and I feel no right to intrude upon his private struggles and thoughts. On the other hand, Franz Kafka asked Max Brod to destroy all his work; famously, and thankfully, this instruction wasn’t followed.

I think the Kafka example is a bit of a red herring. (Indeed, Kafka may have unconsciously consoled himself with the knowledge that Brod wasn’t really to be trusted with this task.) As with Emily Dickinson, I don’t think we are comparing like with like: an artist who has not yet been properly published must rely on others to make good decisions on their behalf. By contrast, you can hardly claim Bishop did not provide a clear precedent. She was clear and precise in the excellent publication decisions she made in her lifetime. But this strange posthumous book remains, in my opinion, an act of inexplicable – if we’re to avoid the armchair psychoanalysis – literary desecration, and while I’m confident that posterity will slough it off, I am sure Bishop’s legacy would be the stronger for it never having happened.

Happy New Year to all our NSP subscribers!

The spring ‘Writing With …’ courses are now both SOLD OUT … But please check the NSP website and the next newsletter for news of upcoming masterclasses, webinars and studios, and hit that subscribe button if you haven’t.

Our Substack is free, and subscribers receive advance notice of all events.

I am so glad I read this - thank you, Lisa Brockwell! - but it leaves me with a deep, seething anger. It is outrageous that someone can publish your private, unfinished work after your death. I felt similar anger when it was felt that some of the language in Roald Dahl's novels for children should be changed so it wouldn't offend people!

Thank you for this piece on Bishop. I’ve wrestled with the issue of her privacy and desire for decorum for many years—first in a 1996 essay in The Bloomsbury Review (link below) and later when writing about that ghastly film about her love life. I so appreciate your sentiments and share your desire to protect Bishop’s perfectionism and privacy.

In my essay, I quoted from an 1883 letter written by Robert Louis Stevenson to his cousin (reprinted in The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson: Vol. II, Greenwood Press, 1969). Stevenson wrote:

“There is but one art--to omit! O if I knew how to omit, I would ask no other knowledge. A man who knew how to omit would make an Iliad of a daily paper.” One can’t help thinking Bishop’s “one art” was the art of perfecting omission.

https://www.academia.edu/4867424/Elizabeth_Bishop_Under_the_Microscope_An_Essay