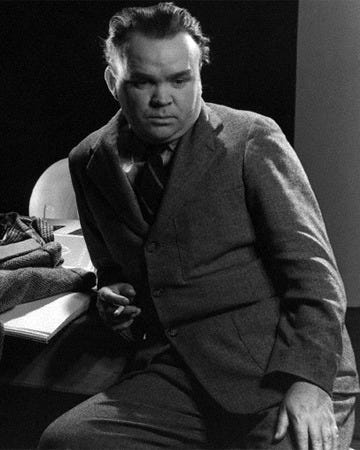

Auden's 'Imaginary Friends'

NSP Guest Post! Andrew Neilson on how the literati cope as Rome falls

It might seem strange to argue that a poem about civilisational collapse contains a secret to the writing of successful poetry, but here we go.

Supposedly composed in response to a challenge by Cyril Connolly to write something that would make him cry, ‘The Fall of Rome’ is one of W. H. Auden’s more evocative later poems (‘later’ in the sense that it comes after his ‘English Auden’ phase, in 1947, once he had moved to the United States). Written as it was in the aftermath of the Second World War, ‘The Fall of Rome’ finds Auden ruminating on the mundane details of that aforementioned civilisational collapse. The poem uses temporal anachronism and a cinematic shifting of scene (Auden, whose commentary for John Grierson’s documentary Night Mail is a prototype for the film-poem, was instinctively cinematic as a poet) to zoom in and out of perspectives: “The piers are pummelled by the waves/In a lonely field the rain/Lashes an abandoned train”…”As an unimportant clerk/Writes I DO NOT LIKE MY WORK/On a pink official form”. All of this culminates in one of the most spectacular finales in 20th-century poetry, where the elegiac tetrameter quatrain of Tennyson’s In Memoriam is pushed to bravura heights of agility and stanzaic compression:

Altogether elsewhere, vast

Herds of reindeer move across

Miles and miles of golden moss,

Silently and very fast.

With so much readerly attention being drawn to the rhythm and rhyme of formal poems, increasingly so as they become ever more unusual in contemporary verse, not nearly enough attention is paid to the sentences running through that rhythm and rhyme. Sometimes the magic can be found in the stringing of syntax, of sentence-meaning, across the stanzas. But here, in the final stanza of ‘The Fall of Rome’, a very large amount of work is done by the placing of a single comma in the opening line.

Altogether elsewhere ... well, in the middle of the poem, comes this stanza:

Private rites of magic send

The temple prostitutes to sleep;

All the literati keep

An imaginary friend.

Given ‘The Fall of Rome’ is a series of vignettes either illustrating a sense of decline and decadence (those ‘temple prostitutes’), or contrasting the frailty of human civilisation with the immense forces and patterns of the natural world, it is common to read the mention of the literati and their imaginary friends as a further sign of the societal decay being portrayed. The esteemed editors of this platform ran these lines past AI and the bot talk is as follows:

The literati are talking to voices in their heads while roads go unmaintained, soldiers desert, provinces drift away. Culture becomes a closed circuit. He [Auden] is skewering the kind of inwardness that mistakes self-dialogue for civic engagement.

This is perfectly plausible but it’s worth saying that Auden himself had taken something of a turn from civic engagement after forswearing much of his political poetry of the 1930s (see a fine recent essay on this, and on Yeats and Eliot, by Colm Tóibín in the London Review of Books). And using a phrase like “the literati”, with its high-brow and rarefied connotations, seems hardly to need the introduction of imaginary friends to suggest atomisation and insularity. A certain redundancy is risked and Auden, at least at this stage in his career, tended to avoid redundancies – especially so when working within such a small canvas as this poem.

What’s more, the redundancy is arguably heaped upon with the opening of the following stanza: “Cerebrotonic Cato may/Extol the ancient disciplines”. The word drawing attention to itself there means a personality type drawn towards intellectualism and introversion. Do we really need the literati and their imaginary friends to prefigure this in the couple of lines just before?

A characteristically droll alternative is provided by the poet Anthony Hecht, in his study of Auden’s poetry, The Hidden Law:

[…] Auden may be playing upon the complex and deceptive practice of the classical poets of addressing their amatory poems to persons represented under fictive names, like Celia, Delia, Lesbia, etc., a practice continued by such neoclassical poets as Jonson and Herrick, as well as others. The device is a tribute to the practice of earlier poets, who in this way were able to secure the anonymity of the married women with whom they were having affairs. The device also made it possible to pretend to be having an affair even if one wasn’t, and to endow the beloved, whether real or not, with exceptional charms which needn’t have borne any relation to reality.

This reading manages to be both straightforward and “complex and deceptive” all at the same time.

Let’s keep that sense of writerly deceit in mind but return to the idea of atomisation. When Auden wrote his poem, the war economy that had won the Western Powers their victory was only just metamorphosing into what would become known as ‘late capitalism’. But he is already meditating on what is happening to society, and the world of work, in those lines about the “unimportant clerk”. As Hecht points out, Auden’s definition of a ‘worker’ (in his commonplace book, A Certain World) is that of someone who is “personally interested in the job which society pays him to do”, and not that of a “wage slave”. For Auden’s worker, “what from the point of view of society is necessary labor is from his own point of view voluntary play”. With that as context, Auden goes on to ask a question first published over a half a century ago, in 1970:

What percentage of the population in a modern technological society are, like myself, in the fortunate position of being workers? At a guess I would say sixteen percent, and I do not think that figure is likely to get much bigger in the future.

Without belabouring the point, for what passes as a member of the literati today, crushed on all sides by dwindling sales and diminished retail space, by shortened attention spans and FAKE NEWS, it might be understandable to cultivate an “imaginary friend”, or in other words, an ideal sense of ‘the reader’. That goes double for the poets.

There are some people (particularly in poetry, with its aesthetic pretensions and apparent disdain for marketing) who claim writing for a reader is a mistake, that it imposes unreasonable objective expectations on their subjective artistic expression, that one should place primacy on the writing impulse and leave the audience to organise themselves. As even Auden seems to concede, writing is “voluntary play”. It is possible these people are kidding themselves, and others, but if they are being sincere then they are playing on their own, without any imaginary friends. Just ask any small child if that’s a good idea.

If, on the other hand, writing for a reader imposes some rules on the play, perhaps that’s for the best. They are the rules of friendship, after all. In this reading, all the literati should indeed keep an imaginary friend. It makes the writing more likely to be any or all of the following: to be entertaining, to be edifying, to be … excellent.

And here’s the thing. Poets have always written for an imaginary friend, and not just in the specific mode of literary address that Anthony Hecht refers to. Poets write, in a conversation of influence and allusion, with poets that went before them – and given those poets tend to be dead, any friendship being forged is by definition imaginary. At the same time, implicit in the idea of posterity is the sense of writing for readers that are not yet born. Whose “sleeping head”, in his ‘Lullaby’, is being asked to lie, “human”, on Auden’s “faithless arm”? Or, to use perhaps the single best example in literature, who do you think John Keats is holding out his “living hand, now warm and capable” towards? Clue: he only goes and tells you.

Andrew Neilson was born in Edinburgh and lives in London. He works in prison reform and co-edits the digital poetry journal, Bad Lilies, with Kathryn Gray. A pamphlet, Summers Are Other, was published by Rack Press in 2025. His debut collection, Little Griefs, is out in March from Blue Diode Press.

The spring ‘Writing With …’ courses are now both SOLD OUT … But check the next bulletin for news of new classes. Hit that subscribe button if you haven’t, and it’ll land in your inbox. A few places are left for Don Paterson’s Sunday Morning Reading Circle mini-series – click here for details!

Our Substack is free, and subscribers receive advance notice of all workshops, studios, masterclasses and events.

Amen to this, and thanks, on Auden's great poem. I often think of Robert Lowell's remark that 'every poet has a thousand readers, all of whom think they are the only one'. Poems speak intimately to that one ideal reader.

Thank you for this lively post, read over here from within the falling empire. (I love the quirky particularity of Auden's 16% --not 15%, not 20%--who are "workers." What would we say it is today? Smaller, indeed.)