A Bit of a Performance

John Glenday on the ins and outs of reading poetry to the public

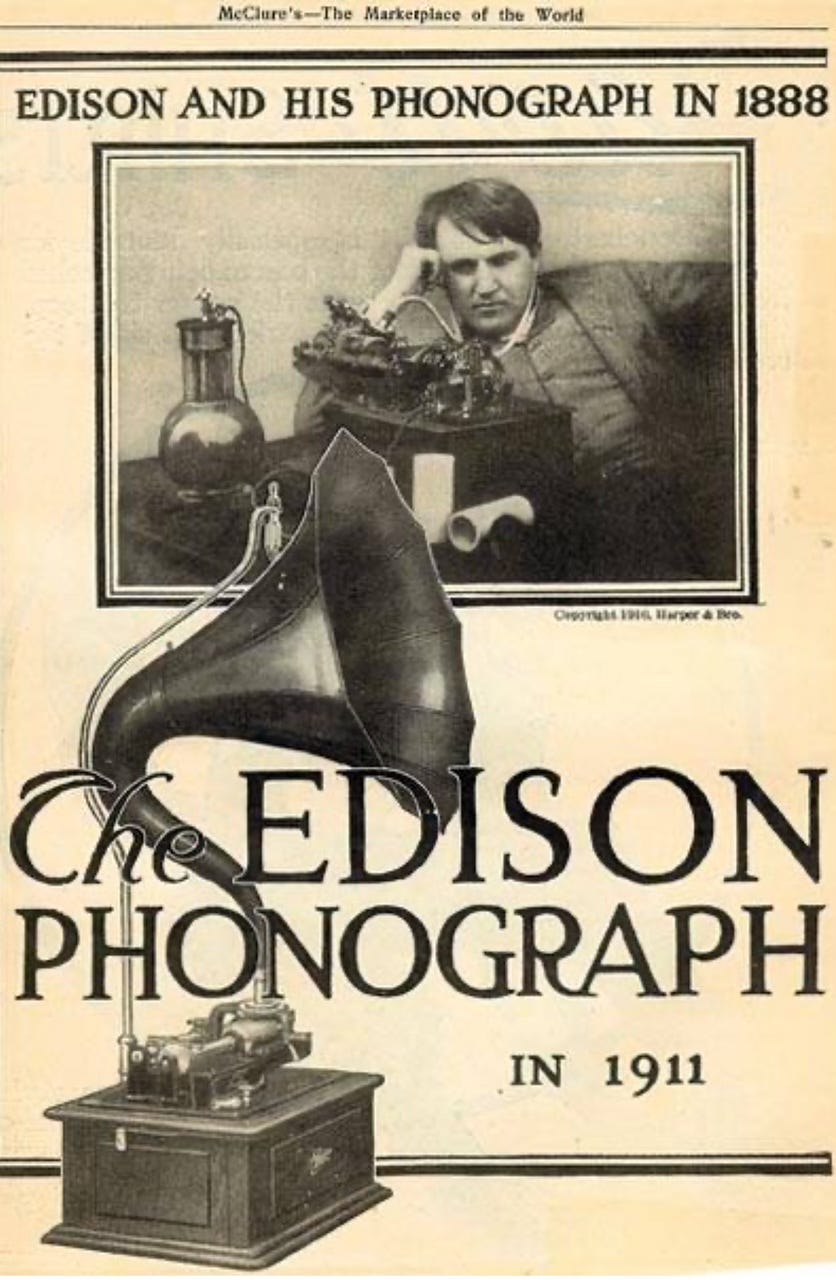

The very first recording of a poem being recited, if you discount Edison's ‘Mary had a Little Lamb' of 1877, is Robert Browning in 1889 on a hand-cranked Edison cylinder. He's rollicking out 'How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix' in a digestive biscuity voice. The clatter of the rotating cylinder sounds just like galloping horses.

There's also a fair bit of background noise to Tennyson declaiming the Charge of the Light Brigade in his disconcertingly upper-class register, pitched so that we can’t forget that in those days poetry came down to us from a higher plane. Likewise, I suspect it would be hard for most modern audiences to tolerate Yeats intoning The Lake Isle of Innisfree, intent on avoiding speaking poetry as if it were prose. This is the man who spent his life 'clearing out of poetry every phrase written for the eye, and bringing all back to syntax, that is for ear alone.'

My very first public reading was at the Scottish Association for the Speaking of Verse, in 1984 or 1985, their Diamond Jubilee Poetry Competition. I'd written a very mediocre poem in Scots which I had to read out at the presentation. Fortunately, I remember little of the event other than mumbling the lines quietly and very quickly into the trembling lectern while the audience fidgeted and coughed. The presentation was made by the formidable Norman MacCaig, who introduced the awards: 'I've been told to say there were many fine entries in this competition. There weren't. I've been told to say it was difficult choosing a winner. It wasn't.'

I've worked on my technique since then by trying to remember there's an audience out there, and rather than being myself, I pretend to be myself. The myself that is comfortable speaking in public. Performance is a form of acting, of pretence, and I've always found the poets who just seemed to be themselves were the most enjoyable. MacCaig was one of the most popular performers of 20th century Scottish poetry - I heard him read many times - but his readings were often just a tad too performative for my liking - however good the poems might be, it was too obvious that he was presenting a cartoonish version of himself - McCaig with that extra 'a'.

In contrast, when Jackie Kay read in Dundee as part of her Adoption Papers tour - must have been 1994/5 - what struck me was not just the poetry, which was moving, but that she came across as, well, herself - a real person reading real poetry. She played that part well. That sort of stage presence is perhaps a gift. Heaney had it. Maya Angelou had it. Adrienne Rich, in her eighties, crippled with arthritis, had it. Listen to Ishion Hutchinson reading The Mud Sermon - he definitely has it. But the not-so-good can be very not-so-good. I've endured many seemingly endless readings by stablemates of Colin the energy vampire. Fine poets don't make for fine readings. ---------, such an outstanding poet that I don't want to name him here, never seemed capable of doing justice to his work on stage. And out there somewhere in a class of his own, the late Peter Reading, of whom C K Stead wrote:

'Have you a story?'//Every poet who has read/with Reading/has one./Mine (two)/are from King's Lynn.//Here's the first...'

There's a perception that 'performance' poetry and 'page' poetry are at either end of a spectrum; that the one is built to withstand the pressures of the stage, while the other thrives in the quietude of printed matter, but there's a fascinating middle ground here. There are performance poems I think stand up well to the rigours of the printed page, though many others wilt at a second reading. And there are poems that thrive on the page but just don't work read aloud. But that distinction between performance and page poetry is to some extent a notional one - I know several amphibious poets who are compelling performers in the air and on the page - just looking at Scotland, Nasim Rebecca Asl and Billy Letford are both highly successful at occupying that middle ground.

I definitely have poems which work on the page, but I'd never inflict on an audience, and poems which lie limp against the page, though they seem to go down well enough at a reading. The performed poem gets one shot at making contact with the audience. It relies heavily on a combination of energy and accessibility mediated by the strength of the performer's delivery and their charisma. The page-poem on the other hand, in all its depth and richness can be read and reread at leisure. Or not. I admired the way Heaney would occasionally give a short poem a second run when he was onstage: 'I'm just going to read that poem again...'.

And then of course there's actors 'performing' poems - what about Richard Burton or Anthony Hopkins or Tom Hiddleston or Jonathan Pryce or Michael Caine or Benjamin Zephaniah or Michael Sheen or Iggy Pop or - God forbid - Dylan Thomas himself reading 'Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night'? Or Morgan Freeman sonorously misspeaking 'Invictus' or Fozzie Bear and Gonzo singing 'Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening' to the tune of Hernando's Hideaway? (I know which is my favourite and it would have Frost spinning in his grave). The difficulty here is that the actor doesn't appreciate that emotional heft and resonance are intrinsic elements of a successful poem, not something added afterwards, like sprinkles. That's why, with a few exceptions, they're better off reciting the Yellow Pages than a great poem.

Some poets are born to perform; some slowly acquire the art. Some are never comfortable doing that reading to an audience thing, others will read their work out loud at the drop of a hat. I don't dread it now, mainly because I don't do enough readings to bore myself, let alone an audience. I delude myself that it's the closest I come to my readers, though almost all the audience response, apart from the occasional nod and 'Hmm', lies in the carefully rehearsed spontaneous jokes I sandwich in between the serious stuff.

Of course we all know what happened with Robert Browning and that recording. After a couple of lines, he falters and forgets his own poem. What does he do? He apologises, then in a fit of boyish enthusiasm, calls out 'Robert Browning! Robert Browning!’ He just can't resist getting his name in there. And the poem? It's still galloping south, laden with good news, riderless, into history.

🌊 All current North Sea Poets courses are sold out, but we’ll have news of new webinars and masterclasses for the autumn in the next newsletter. 🌊

Get all the details at northseapoets.com 🌊

You reminded me of the launch of an Italian edition of MacCaig's Selected Poems. By then Norman was too ill to read himself, and Valerie Gillies stood in for him – graciously, if quietly. Norman sat near the back, and then complained loudly throughout that he couldn't hear himself at all. This was the only time I've ever seen anyone heckle their own poetry reading. Then there was the time Norman was sharing a platform with Sorley MacLean. He became increasingly irritated over the length of time Sorley spent leafing through his books to find his next poem.‘Sorley – I believe you’re supposed to read them aloud.’

Loved this - particularly as John Glenda’s was the guest poet yesterday evening at the online monthly open mic of Fire River Poets based in Taunton! His reading was so enjoyable and so were the bits in between! A fantastic evening!